Focus on Outcomes — Centre on Students: Perspectives on Evolving Ontario's University Funding Model

- Foreword

- Time for Transformation

- What We Heard

- What We Learned

- Strategic Directions: Focus on Outcomes, Centre on Students

- Further Observations

- Next Steps

- Appendix A: What Else Was Heard

- Appendix B: Select Metrics

- Appendix C: List of Participants

- Footnotes

- The Report at a Glance

The complete report is available as a PDF (1.3 MB) | Report At A Glance (PDF, 229 Kb)

Foreword

It was a privilege to lead this consultation on the future directions for the province’s university funding formula. In the space of a few very busy months, we heard from a wide range of stakeholders who are as passionate about the issues of postsecondary education as they are insightful about the factors shaping the sector’s future.

The quality of the contributions we received – their depth and thoughtfulness – made it both easy and challenging to compile this final report. Easy, in that the reasoning behind each position was clear and well substantiated, but challenging in that the various positions had to be synthesized into a compact format.

One clear finding emerged from the consultation despite the range of positions put forward: that student success is a shared goal for all stakeholders. Our strategic directions capitalize on and harness this commitment, aiming to promote a culture of continuous improvement with respect to student outcomes. A reformed funding formula should support students and foster universities’ economic and social contributions.

I thank everyone who took the time to participate and share their views. I look forward to seeing what will take shape as the province weighs the advice in this report. I would also like to extend my personal thanks to a small team of advisors who assisted me in this process. Under the leadership of Bill Praamsma, and with the support of Chris Martin, Lindsay DeClou, Liliya Bogutska and Api Panchalingam, we have been able to accomplish a great deal in a short period of time. It’s been a pleasure to work again with public servants whose commitment and quality are exceptional.

Sincerely,

Suzanne Herbert

Executive Lead, Consultation on University Funding Model Reform

Table of Contents / Top of Section

The province no longer funds “universities” per se. It funds quantifiable outcome(s) or achievement(s) it wants from universities for the betterment of the public good. The things to be measured and applied to determining funding shares must be the outcomes that matter to Ontario. In the past, this has been enrolment growth. Today, as identified in government policy and consultation papers, they are measures of “quality” and “improving the student experience”.

Design Questions: Funding Models for Ontario (Toronto: Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario, 2015), p. 2.

Time for Modernization

Ontario’s university sector has experienced unprecedented growth over the past 15 years. Demand for postsecondary education has grown quickly. With government support, universities have responded by expanding their programs. Students have also benefitted from one of Canada’s most generous student financial assistance systems – and from a government commitment to support all qualified students in pursuing their goals.

Yet with smaller numbers of secondary school graduates expected in the coming years, enrolment growth is predicted to slow. Universities anticipate pressure on their budgets as a result: enrolments are their main source of operating revenues through both student fees and government grants. Enrolment growth will no longer provide the increased revenues that universities need to cover rising costs.

At the same time, questions are being raised about the value and purpose of undergraduate degrees, the quality of education students are receiving, and the ability of university graduates to successfully demonstrate their learning in a work environment.

All of these factors are amplified by the fact that the postsecondary education sector is more competitive today than perhaps it has ever been.

Up to Now: Building a Framework

Released in 2013, Ontario’s Differentiation Policy Framework for Postsecondary Education set out the following objectives for the postsecondary education sector:

- Shift the focus of institutions away from enrolment growth

- Reduce unnecessary duplication

- Ensure that institutions’ mandates align with government priorities

- Reinforce the role of the Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities as a steward of the system

After releasing the Framework, the government negotiated and signed Strategic Mandate Agreements with all 45 publicly assisted colleges and universities in Ontario. These Strategic Mandate Agreements included a commitment to reform Ontario’s university funding model.

Funding universities in a quality-driven, sustainable and transparent way is a key part of the province’s economic plan. In March 2015, the government announced it would advance the transformation agenda with consultations on modernizing the university funding model.

Ontario’s Current Funding Model

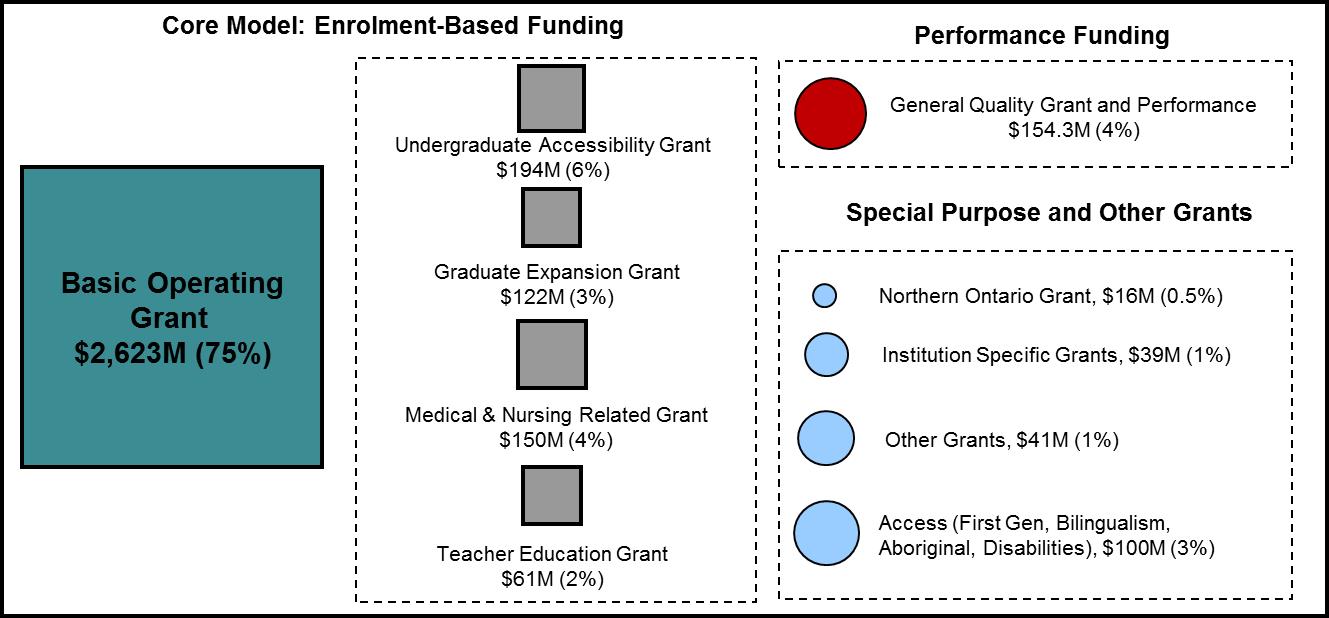

The purpose of the funding model is to provide a fair and balanced method for determining the share of the provincial operating grant to be allocated to each institution. The Ontario university funding model aims to ensure a reasonable degree of equity in the distribution of available government support, but does not determine the overall level of funding in the system. The current funding model distributed grants for 2015–16 in the following manner:

The funding model consists of three main components:

- The core model, which is enrolment-based, is composed of several parts. It includes the Basic Operating Grant, which provides grants based on historical enrolments and is intended to provide a level of stability and predictability that allows universities to do multi-year planning. Three other grants support new enrolment and growth: the Undergraduate Accessibility Grant, the Graduate Expansion Grant, and the Medical and Nursing Related Grant. Lastly, the Teacher Education Grant supports both new and historic enrolment in teacher education programs. Funded enrolments for graduate, medical and teacher education are capped by the ministry. Together, core grants support current funded enrolment levels.

- Performance funding, which is based on key performance indicators (KPIs) and the submission of annual Multi-Year Accountability Agreement (MYAA) Report Backs. Current KPIs include the graduation rate, and the employment rate six months and two years after graduation. Once MYAAs are successfully completed and submitted, an institution’s allocation is determined based on its share of system enrolment.

- Special purpose and other grants, which support specific policy objectives, as well as providing incremental funding to meet the needs of students and institutions.

With few exceptions, universities have full fiduciary responsibility for how operating grants are spent within the university. For grants other than the Basic Operating Grant, universities are required to submit reports that outline how funds were used, but decisions about expenditures are at the discretion of the university.

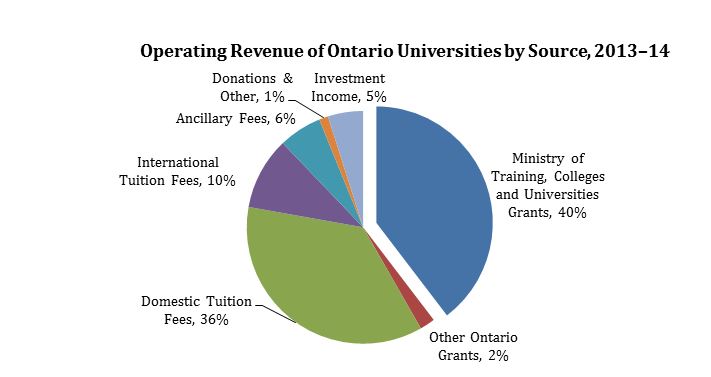

Ontario grants account for, on average, approximately 42 per cent of operating revenue in the university sector; other significant sources of operating revenue are student tuition and miscellaneous fees. The Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities also invests in specific capital projects and student financial assistance, while the Ministry of Research and Innovation invests in sponsored research. Operating revenue does not include funds from sponsored research, endowments, trust funds or capital grants. Student financial assistance provided through tax credits, the Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP) and institutional financial aid is also held outside of the scope of Ontario universities’ operating revenues.

Consulting the Sector

In spring 2015, the ministry launched an open and transparent consultation on university funding model reform. The process explored ways in which Ontario’s university sector could enhance quality and improve the overall student experience; support the existing differentiation process; increase transparency and accountability; and address financial sustainability – all within the scope of the ministry’s operating grants, which totalled about $3.5 billion.

The aim of the consultation was not to design and deliver a new funding formula, but rather to allow for a conversation that would yield the best advice to the government about how to reform the funding model. The exercise was not about finding a way to reduce the government’s contribution, but at the same time new funding was not anticipated.

A wide range of stakeholders were engaged, including university senior administrators, students and faculty, college representatives, employers and staff associations, and elementary and secondary educators. Some 175 participants attended the consultation’s all-day event on May 6, 2015, breaking out into groups for facilitated discussions. More than 25 shorter-format events were also held over the course of the consultation. In total, stakeholders prepared over 20 written submissions by the end of the consultation process.

A reference group of sector experts provided high-level advice on funding model design and the student experience. Joint briefings were held openly with key stakeholders on a variety of topics: health system funding reform, the Ontario Municipal Partnership Fund, Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario perspectives, and the current university funding model. Additional discussions looked at the college, child welfare and school board sectors.

The consultation process revealed common challenges, illuminated good ideas and brought attention to initiatives already underway to address relevant issues. A survey of university funding formulas used in other provinces and countries put Ontario’s approach in a wider context and underscored the variety of potential funding approaches.

The commitment to openness and transparency was supported by regular meetings with key stakeholders. Briefing material was publicly available, and a blog provided updates on the status of the consultation, which officially concluded on September 1, 2015.

Distilling the Findings: An Introduction to the Report Structure

The themes in this report are drawn from summaries of the all-day consultation event, internal and external meetings, reference group meetings and formal stakeholder submissions. The views of those who participated in the all-day event were validated by the facilitators, note-takers and stakeholders who took part.

The structure of this report is designed to accomplish two objectives – first, to report on the results of this broad consultation, and, second, to offer strategic directions for the ministry to move forward. Although it is possible to skip to the back of the report, it is not recommended. A key feature of this engagement was the breadth and diversity of views that was unearthed. This report presents a thorough attempt to represent all the perspectives of the participants.

In this report, the themes are organized according to four policy principles: quality and the student experience; differentiation; transparency and accountability; and financial sustainability. The document itself is divided into three parts:

- What We Heard

- What feedback was heard throughout the consultation?

- What We learned

- How does that feedback relate to the policy principles?

- Strategic Directions

- What directions should be taken in Ontario's approach to funding model design?

While recurring comments and feedback have been synthesized in this report, no formal counting methodology has been applied. Throughout the consultation, feedback sessions were held to confirm and share the main themes with key stakeholders. Some subjects raised during the consultations were out of scope, including tuition, collective bargaining, pension reform and adequacy of funding.

Table of Contents / Top of Section

What We Heard

Because of the range of participants and stakeholders involved in the consultation, input was diverse and sometimes contradictory. The goal of this report has been to bring focus and coherence to the findings of the consultation without “over-tidying” or misrepresenting the breadth and nuance of perspectives. This summary collects similar ideas while recognizing the variety of viewpoints.

Theme 1: Enhancing Quality and the Overall Student Experience

A high-impact learning experience is one in which a student ‘learns by doing’ tasks related to their academics in an environment that allows for structured learning and critical reflections. These experiences allow for students to apply theoretical skills and insights to real-world, contemporary applications. Similarly, this allows professors and even students to bring such practical examples into the classroom in an impactful way.

Formulating Change: Recommendations for Ontario’s University Funding Formula Reform (Toronto: Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance, 2015), p. 24.

Sector stakeholders generally believe the quality of postsecondary education in Ontario needs sustained improvement. While they differ over what should be done or how to measure quality, they mostly agree that measurement is important to ensuring positive outcomes. Many universities felt hesitant about having a single, system-wide approach that could overlook meaningful differences between institutions and their programs.

Defining and measuring quality is difficult

Quality tended to be defined in terms of the teaching and learning experience. Some participants said there needs to be more attention to teaching, especially at the undergraduate level; others suggested that teaching quality is threatened by the shift towards more sessional and fewer tenure-track faculty members. Many saw faculty renewal as a way to improve teaching quality; the trend towards later retirement was seen as an impediment and a source of fiscal pressure.

Some felt measuring for quality improvements would be unfair, given that certain institutions have more room to improve than others. As well, there was some reluctance to tie funding to learning outcomes when there is no certainty about whether those outcomes can be achieved.

Other participants suggested learning outcomes should focus on transferable skills such as communication, leadership, problem solving and critical thinking. The perception was that students aren’t always aware of such skills even when they acquire them, and as a result, they may not be able to describe them when seeking employment. Some felt that for employers, who wantjob-ready graduates, transferable skills could be a starting point but work-related training was also required. It was suggested that identified metrics could be prioritized and published so that students and stakeholders, such as employers, have a common understanding of what a university education should deliver.

Caution against relying on labour market outcomes as a benchmark for the value of a university education was raised by some. Since broader economic factors are outside of the control of universities, they were considered to be an unfair measure of university performance. Too much focus on labour market outcomes was also seen to risk devaluing the social and civic benefits that Ontario universities provide. Some said funding could be tied to outcomes that represent the “whole student experience” – focusing not only on academic program delivery, but also on vital services that support effective learning and research environments. This would require Ontario to adopt teaching and learning practices that would make it more competitive in the knowledge economy.

Given all the discussion about measurement and which outcomes are most appropriate, many felt that adopting an outcomes-based approach would likely require more work with the sector. As well, participants noted that measurement is not “resource-neutral” for universities and would need to be considered in any new funding model.

Student success is still the priority

Student success, which is a long-held value of universities, was seen to be affected by many things, including access to educational opportunities, the availability of supports and services, and the quality of the learning experience itself.

Many respondents said that maintaining a broad range of university programs is important to ensuring access. Several felt funding reform should encourage a holistic, interdisciplinary approach that takes into consideration the longer-term social and economic impact of postsecondary education, instead of focusing on short-term labour market needs. Some said putting too much weight on labour market needs will “corporatize” universities, impede their public mission and restrict their comprehensiveness. Others felt the funding formula should give greater priority to liberal arts and science education, and to the sustainability of all universities providing foundational BA and BSc programs.

Student choice was also perceived to be driving change on campuses. Participants said universities are under increasing pressure to provide high-quality teaching, learning and research experiences to attract students from Ontario and beyond. Many felt student experiences were increasingly driven by a “consumer” orientation.

In addition to breadth, participants felt universities should offer more flexibility so that students can balance their studies with other life commitments. Course scheduling and online delivery was seen to play a role here, with the caveat that face-to-face interactions remain important and that learning should not occur exclusively online.

Strong services contribute to student success

Many students were seen to face significant social, economic and psychological pressures that limit their time and capacity for learning. Respondents said universities need to invest more in student services, which they fear are not prioritized enough within the university budget. These services, both academic and wellness-related, include counselling, tutoring, orientation and campus security. Participants spoke about mental health as an issue that consumes significant institutional resources, and said support in this area needs to continue. As some noted, for continued student success, services need to be available throughout the entire program.

Participants revealed that specific services are necessary to make university education more accessible to underrepresented groups – such as Aboriginal persons, first-generation students and students with disabilities – and to provide more program offerings in French. Part-time students also tend to have diverse needs: some felt the new formula should set aside money to support part-time students, for example for financial aid programs or services such as on-campus childcare. Mature students were another group identified as requiring better funding support. Many participants in the consultation said that while accessibility initiatives should focus on at-risk students, general enrolment growth should also continue to be a goal.

Supporting innovative programming and quality infrastructure

Further adoption of evidence-based teaching and learning approaches, such as active learning classrooms, experiential and technology-enhanced learning, entrepreneurial thinking, and modern laboratory and performance facilities, was put forward as one way to enhance the student experience. Participants suggested that some predictable portions of funding could be tied to the delivery of high-quality, innovative programs that can be measured against objective, transparent and agreed-upon criteria.

As the physical environment plays a role in students’ university experience, several contributions to the consultation pointed out the need to deal with the deterioration of on-campus infrastructure caused by time, wear and redirection of funding to other priorities. The perception was that poor infrastructure affects accessibility and has a negative impact on program delivery and the well-being of students and university staff. Increasing the level of special purpose, restricted-use funding was suggested to target these priorities.

Good job conditions contribute to a better student experience

Respondents said universities should have adequate funding to support good jobs on their campuses. “Good jobs” was seen to mean fair terms and conditions for contract faculty and sufficient numbers of tenure-stream faculty to maintain reasonable workloads.

Some said the funding formula should recognize the integral role played by Ontario’s thousands of university support workers, many of whom deliver important services that contribute to student success. Suggestions included building non-academic staff into the funding model to help acknowledge their importance and at the same time provide a way of tracking how steady and continuous many of these “part-time” or “contractual” jobs are.

While some participants called for more sessional lecturers and, specifically, for private-sector talent to deliver entrepreneurial education, others recommended limiting the proportion of institutional funding that can be spent on contract academic staff.

Preparing students for employment

Employment readiness and value for money were among key concerns raised by consultation participants. Some said universities need to focus more on developing skills that match job expectations, as measured by students’ knowledge of a specific discipline when they graduate. Certain participants said aligning university education with dynamic, hard-to-predict labour market trends would be a challenge, especially given the limited information available.

Experiential learning, including work-integrated learning, was seen to support the employment objective. Some participants felt universities should be rewarded for providing such opportunities. Others said the ministry has a role to play in securing industry partnerships that will help remove barriers between students, universities and employers.

Outcomes matter, but opinions vary about how to weigh them

Participants widely agreed that focusing more on student outcomes is important: a funding formula based solely on enrolment creates challenges for universities with respect to improving quality. Many suggested that Ontario’s significant success in achieving postsecondary education access goals presents the opportunity to refocus on enhancing quality and student experience. In the face of demographic declines, some said institutions should be incentivized to put a greater focus on student outcomes.

While many said greater focus on student outcomes was important in order to move the discussion beyond enrolment, there was less agreement on how much weight outcomes or performance should be given in the new funding model. It was suggested that the ministry will first need to determine how to measure performance, with tools that are tested and proven by experience before being used to determine funding. Some pointed to retention as an important indicator, saying the new funding formula should look at student progress – especially whether or not students transitioning from secondary school advance beyond the first year of university.

Others warned that performance-based funding brings risk of “perverse incentives”, ignores cost differences involved in improving performance for different students, could undermine institutional diversity, could shift focus away from long-term outcomes and cycles, and could reduce stability for universities. Some said that while there is “nothing wrong” with creating incentives through postsecondary education funding, performance-based funding has not proven to be the best vehicle. Others said funding should always aim to create the conditions for excellent program delivery and student experience, and not be punitive in any way.

Theme 2: Supporting the Existing Differentiation Process

Many participants said differentiation is a powerful tool for achieving quality in postsecondary education by focusing on universities’ strengths and reducing unnecessary duplication. Some noted that while there may be an overall set of provincial objectives for the sector, the contributions of individual institutions should be varied and, to some degree, unique.

Focusing on university strengths

The consultation revealed that the differentiation agenda could take various directions. While many felt the new funding formula should not pursue a one-size-fits-all approach to recognize institutional strengths, others were more specific about how a funding formula could achieve and promote institution-specific differentiation and specialization.

Most agreed the new funding model should recognize each university’s distinctive role in the province, and that metrics should reflect that differentiation. The perception was that any qualitative or quantitative assessment should take into account an institution’s mission, goals and circumstances.

Supporting regional diversity

Some participants recommended using the funding formula to encourage regional differentiation or differentiation among clusters of universities and colleges. There were multiple reasons why this was considered important – the relative social and economic impact of different universities in different regions is large. As some respondents noted, the province has many related policies with regional implications, and universities should align with these, which include Ontario’s Policy Framework for French-Language Postsecondary Education and Training, Ontario’s Aboriginal Postsecondary and Training Policy Framework and the Growth Plan for Northern Ontario. Many who supported the recognition of regional differentiation in the university funding formula also said partnerships with local industry should be encouraged and supported because they strengthen regional economies and benefit communities.

Opinions on the use of grants to support differentiation were mixed. Some said the province should stop funding with one-off grants and adopt a more comprehensive model. Others said the new funding formula should maintain and expand existing special purpose grants to support rural and northern universities and increase access to postsecondary education for francophone and Aboriginal populations. Questions were raised about provincial approval of small universities that were seen to be not economically viable.

Some participants said a regionally differentiated approach might limit the educational opportunities available to students who cannot afford to move away from their community to attend university. Some said supporting small institutions, especially those in small communities, is crucial to maintaining regional diversity, and that opportunities for broad programming, travel grants and cross-subsidization need to be considered.

Excellence in research and graduate education should be supported

The core activities of any university are teaching and research, and participants agreed the funding formula needs to promote both. Many supported greater integration of research into the undergraduate learning experience. A greater collaboration between universities was seen as necessary for many to compete globally. It was remarked that international students are well aware of international rankings, which are largely based on research metrics, and that Ontario universities need to adopt this global viewpoint in order to compete.

While the quality discussions highlighted the need to improve undergraduate education, when it came time to talk about differentiation, many respondents said the funding model should prioritize graduate studies, building on prior investments by the Government of Ontario. PhD studies already receive stronger weighting, but some said this is not a good way to differentiate research and suggested that dedicated research funding should be considered. Others suggested that research funding provided by the Ministry of Research and Innovation and Ministry of Economic Development, Employment and Infrastructure should be considered as part of the province’s university funding review.

The consultation drew attention to the fact that indirect costs related to research activity place a significant strain on universities’ operating budgets. Participants said that indirect costs arise from the infrastructure needed to support research projects – anything from information technology and library support to administration and human resources. Both Ontario and the federal government have grants that support indirect research costs, but many participants argued this support is inadequate and diverts scarce dollars from other purposes.

Strategic Mandate Agreements help drive differentiation

Many participants agreed that Strategic Mandate Agreements are the ministry’s best available tools for setting performance-based funding metrics and furthering differentiation, especially once institutions see they will be rewarded for differentiated efforts. Others said competition could actually lead universities to become less differentiated, at least when competing for certain types of program funding, e.g., in STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and math).

Some said the Strategic Mandate Agreements would be most effective at tying funding to general performance outcomes. Mapping all metrics would help start a dialogue on how to approach any identified gaps. It was suggested that substantial funding should be tied to the fulfillment of Strategic Mandate Agreements in any new funding formula.

Many agreed the SMA process needs improvement and should align with any funding formula. Some participants said future Strategic Mandate Agreements should include quantitative and qualitative measures – but that only a small proportion of an institution’s funding should be tied to those measures.

Finally, respondents said enrolment levels should be negotiated between universities and the government, with sensitivity to demographic realities. At least one participant said the ministry may wish to have an opinion about optimal enrolment levels by program area, although it was acknowledged that evidence-based targets can be difficult to produce.

Outcomes-based funding could support differentiation

Consultation participants saw value in linking outcomes to funding as a driver of differentiation. At the same time, many emphasized the importance of balancing outcomes measurement with institutional and system-wide measures. Some respondents argued that any metrics should be developed in consultation with institutions and reflect differentiated characteristics rather than generating absolute comparison with other universities. Necessary developmental work was seen to be needed before linking outcomes to funding to ensure that diversity of missions is not undermined by standardized metrics.

Other suggestions included measuring outcomes that are in the institutions’ control, such as graduation rates, and avoiding outcome measures that are not in the institutions’ control. As one respondent noted, institutions should be allowed to add their own metrics: the outcomes might be common goals, but how they are achieved could vary from institution to institution. Specific context needs to be factored in when establishing system-wide metrics.

Theme 3: Increasing Transparency and Accountability

The availability of comprehensive and accessible data is crucial to the higher education sector’s ability to engage in well-informed policy discussions and decision-making processes. An improved data environment would support the work of sector stakeholders towards ongoing improvements at Ontario’s universities.

Building on strengths, addressing weaknesses

(Toronto: Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations, 2015), p. 16.

Participants agreed the funding system should be transparent to institutions and the public, though some said it was not totally clear what “transparency” means in this context – whether it refers to transparency of financing, student outcomes, government control or something else. That said, it was generally acknowledged that the funding allocation formula must be objective and easy to understand and administer.

Strengthening transparency

Many consultation participants made it clear that students need comprehensive information on universities to inform their decisions. Key information on universities that students can access and easily compare was seen to be crucial to ensure that institutions stay accountable.

Respondents also said transparency should extend to implementation of the new funding formula, facilitated by ongoing consultations with university leaders. The need to take a phased, long-term implementation approach was raised on many occasions.

Many participants emphasized that the ministry needs to be clear and more direct when communicating its objectives for postsecondary education sector transformation. As some suggested, establishing clear goals will narrow the range of potential funding approaches and help resolve any perceived inequities. For example, if government priorities require certain universities to receive more funds than others for similar services, the basis for those differences should be transparent and the additional funds should be disbursed through special purpose envelopes or transfer payment agreements – not blended with per-student funding.

Some participants said more transparency is needed to highlight the direct linkages between learning skills and labour market outcomes so that students and employers can make timely and informed choices. Specifically it was remarked that universities need to better communicate the connections between programming and jobs in all disciplines. As a caution, some respondents said transparency will become more challenging if the new funding model incorporates new quality measures, promotes greater differentiation or allows for a more dynamic redistribution of funding shares over time.

The funding formula should be clear

Participants widely agreed that transparency in the current funding formula could be improved, and that current complexities prevent the government from being able to publicly explain funding allocation. Many agreed that establishing a simple, rational funding model with clear metrics and a widely understood methodology would improve transparency. Some suggested moving more monies into core funding – including rolling all accessibility and special grants into the base grant.

At its core, the mechanics of the funding formula have remained similar to the original methodology developed in the 1960s, when the government set tuition fees. As a result, participants in the consultation argued that several components of the formula are now outdated and should be removed, such as the “formula fees” that served as a proxy for tuition many years ago. Other historic issues that arose throughout the consultation include varying levels of per-student funding between institutions in the Basic Operating Grant. Unsurprisingly, many institutions argued for equalizing these varying rates of funding.

The lack of transparency around enrolment in the Basic Operating Grant, and in various growth envelopes (undergraduate, graduate, health-related, and teaching) also created some discussion. Several participants argued for splitting off graduate and broader-public-sector related enrolments (medical, nursing, teaching) from the Basic Operating Grant.

Better data and reporting are needed

Most respondents said that valid and easily accessible data are needed to ensure openness, support system-wide comparisons and enable informed policymaking. Many further submitted that if the province adopts an outcomes- or performance-based funding model – and if it aims to make university funding more transparent – data collection and sharing must be enhanced.

Many respondents felt universities should be expected to release more and better quality data about their internal operations, processes and practices as a condition of public funding. Common examples were information on compensation, administration costs, faculty teaching workloads and the proportion of classes taught by full-time faculty. Some participants said this data should include indicators of accessibility and affordability to measure equity; others recommended employment indicators to measure program delivery. This information should be available not only to government but also to other sector stakeholders and to the public.

Participants felt that, for better data collection, the government should establish a coherent reporting and information housing system and have universities collect a prescribed set of data every year, presented in an accessible, comparable format. If such a system were to be built, some noted it would be important to ensure continued access to data during the process. At the same time, many participants said universities tend to intentionally slow data processes down, with the ministry remaining hesitant to take firm action when imperfections cannot be cleared.

Many consultation respondents said consolidated reporting is needed to improve accountability relationships between universities and the government. Considering the amount of time and resources spent preparing multiple reports, many agreed a streamlined, comprehensive approach would best demonstrate the achievement of key outcomes while eliminating duplication and redundancy. Examples of statistical and enrolment reporting practices in other ministries were cited, such as the Ministry of Education’s Education Finance Information System (EFIS) reports and annual consultations, which provide both accountability and transparency to the public and increase understanding of funding changes year to year. Some participants recommended that before developing a funding formula, the ministry should have the required data collection in place from institutions to inform discussions.

Oversee, don’t overstep

Some respondents said there is currently no accountability to the government for outcomes; others felt the system needs a new accountability approach based on open access, information sharing and comparability that would create outcomes by their very nature. This would not require a change to the funding formula but rather could be made a basic requirement for funding. Others expected accountability to increase with new quality measures, greater differentiation and performance measurement. Most agreed that accountability needs to be balanced with efficiency.

Most contributors said the new funding formula should respect universities’ autonomy and ability to respond to changing societal needs. Others went farther, asserting that more government oversight would not create greater accountability and transparency but rather more instability, as successive governments might seek to impose their own vision of what universities should be doing, creating disruption with every election cycle. As some noted, this would not contribute to the long-term, sustainable and consistent financing universities need.

In general, consultation discussions revealed that flexibility in how to spend provincial funding is important for institutions and should continue to be a major feature of the ministry’s relationship with universities. Participants said there needs to be a balance between using control or micromanagement and flexibility in funding as the basis for stewardship. Many were of an opinion that the ministry needs to trust institutions to spend public funding in an effective and appropriate manner. Some suggested well-performing universities should be rewarded with more flexibility and less Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities oversight, while the consequence of poor performance should be more ministry oversight.

Alignment with government policies is important

Participants agreed on the importance of aligning any new funding model with government policies and initiatives (e.g., tuition, student financial aid, differentiation), especially considering the interdependencies among these. Amid all of this discussion, it became clear the sector has some concerns about the ministry’s capacity to coordinate and implement the transformation of a complex formula covering 20 universities. Participants said it is necessary to consider how the existing funding formula feeds into universities’ internal budgeting processes – and that not doing so will limit the government’s ability to achieve its policy objectives. Some respondents said ministry staff should become more familiar with the operational side of postsecondary education, and questioned who within the ministry would have the time and expertise to engage in challenging negotiations with individual institutions.

Theme 4: Addressing Financial Sustainability

Many participants said operating funding should not be overwhelmingly determined by enrolment if it is going to account for operational realities. Much of the consultation’s discussion about financial sustainability focused on Ontario’s demographic shift, which is shrinking the traditional student pool of high school graduates in the medium-term – presumably resulting in declining or flat growth for many universities. Several participants said the funding formula should not be stretched to try and “fix” the financial sustainability of a few institutions. A view was expressed that many issues may be outside the ability of the funding formula to solve. The inability of universities to keep cost growth down to the level that government is prepared to fund was raised by some.

Ensuring predictability and stability of funding

To ensure sustainability, many participants said stabilization funding should be available for institutions unable to meet their financial obligations because of declining enrolments. Others said the Basic Operating Grant should be used to provide steadiness and predictability across all universities.

Making funding responsive to performance will help achieve long-term outcomes and continued sustainability, according to some participants. Others pointed out that funding cannot be divorced completely from enrolment. A view was expressed that any new model must capture and reflect the costs of providing educational services: costs escalate with size, and enrolment counting is a strong, proven measure of institutional size and therefore expenses. Those asserting size as an indicator of cost said enrolment-based funding should stay at the foundation of the new formula, with any excess as a result of declining enrolments reinvested to bring per-student funding above the national average.

Assessing the international opportunity

The current funding approach to international students was identified as an area of concern, with debate over the pros and cons of including international students in the new formula. While some felt international enrolment helps establish overseas partnerships and grows revenues, others were concerned about the cost of attracting this cohort and becoming financially dependent on international tuition fees.

Funding formula should recognize universities’ cost realities

Many participants said the new funding formula should recognize institutional costs, including the cost of inflation, pension shortfalls and costs related to collective bargaining. Several participants called out the need for inflationary support, as grants have not been increased on this basis for some time. Others said inflationary support should be predictable, and suggested surveying the best practices used to address this issue for other types of organizations.

Respecting autonomy and encouraging collaboration

Many participants saw greater spending autonomy and more collaboration as important to future success and sustainability. They were clear that allowing autonomy would not, for the ministry, be the same as ceding control. Instead, it would be about respecting mature, well-developed institutional planning. Many noted that the funding model should be flexible enough to account for variations in the fiscal environments of universities.

“More collaboration” was perceived as a way of reducing inter-institutional competition and focusing on finding sector-wide efficiencies and avoiding duplicate services and effort. Collaboration was seen to help address the current pressure on colleges to offer more “university-type” delivery and for universities to be more “relevant” and labour-market focused. Finally, some said public/private partnerships present an opportunity to diversify institutional revenue and leverage private-sector investments; although others noted that a greater private-sector role might threaten institutional integrity and academic freedom.

Funding should be fair

Participants agreed that funding should be allocated on a fair and equitable basis to ensure consistent quality across the system and to support student success at all universities. Fair and equitable funding was seen to be responsive to the number of students in the system and “aware” of the programs those students are enrolled in. Some suggested that as enrolments climb, student services, resources and value should all scale up accordingly.

Some respondents said universities should be funded at the same rates for similar activities — which is not the case today. Suggestions included adjusting funding to the mean or median of dollars per fiscal full-time equivalent or dollars per basic income unit.

Current weighting system needs revision

Many participants felt the current program weighting system needs to be revised, or that alternatives should be explored. The current weights were seen to lack an evidence base and to have little known relation to actual program costs. Those in favour of re-weighting argued that program weights should be scaled down or simplified to capture high-level differences.

Others argued that changing program weights should be avoided, given that any change would lead to funding redistribution across the system. The complex internal budgets used by universities led many to caution that it would be impossible to fully predict the impact of these changes. Further, the cost and time that would be involved in such a review was seen to be substantial, with the process having no predictable or clear outcome. Finally, some participants said program weights should be altered for policy purposes, including incentive spending on undergraduate arts and science programs.

Some respondents expressed concern that determining costs is itself too resource-intensive, and that instead the government should focus on the quality of outputs. Others countered this, saying program costing is very doable and that it is important for the government to look at the economics of education, even if the costs are relative and not exact.

Funding model changes must be phased in

Virtually all participants said phased implementation and long-term planning are needed to support universities through funding model transformation, and any new model should be tested before being fully implemented. It was suggested that the first year of implementation be based on existing funding shares to avoid disruptive change. A strong view emerged that universities should be held harmless to avoid major dislocations in funding across the sector, with any changes requiring new money. Some participants recommended significantly increasing the width of the so-called funding corridor to provide stability and predictability when enrolment fluctuates.

Stakeholder-Proposed Mechanisms

Students recommend a new funding formula component be developed to earmark funding specifically for the maintenance and expansion of mental health services on campuses, particularly the availability of therapy and counseling with no up-front costs to students.

Getting it Right for Good(Toronto: Canadian Federation of Students – Ontario, 2015), p. 19.

While the purpose of the consultation was not to define the mechanisms of a new university funding model for Ontario, participants inevitably had some thoughts on the subject. Five ideas are captured below that stakeholders brought forward in some degree of detail:

Consideration of specific institutional needs

Ontario’s university system has several specialized programs and institutions. Some representatives of these programs and institutions noted that the current program weighting often does not fully account for their unique circumstances. In situations where a university and the ministry have agreed that an institution should excel in a specific discipline or program area, participants argued that increased resources should be made available to support this focus.A funding stabilizer to offset the impact of lower enrolments

Considerable support emerged for a revenue stabilizer that would shield universities from the immediate impact of enrolment change. This stabilizer, often referred to as a “corridor”, was proposed in a variety of formats: as a way of maintaining an institution’s funding provided that enrolments remained within a certain percentage range; as an annual limit on funding changes due to declining enrolments; or as a funding “floor” to be maintained while growth is funded as new students enrol. Regardless of the format, widespread support for a funding corridor was clear given a system where some universities face the prospect of substantial revenue changes arising from declining numbers of students.Policy-specific funding

Several participants proposed initiatives that would restrict a certain portion of operating funding to support specific policies and initiatives. In some cases, participants were clear about the purpose of such funding, suggesting it should support mental health and other student services, teaching and learning initiatives, and under-represented groups. Other participants suggested setting aside a proportion of funding for strategic investment priorities chosen by the government on a regular basis, to be allocated via a competitive process.University expenditure caps

Participants concerned about operating budget pressures proposed the province limit the amount or proportion of university budgets that could be spent on certain expenditures. Any expenditure exceeding these limits would result in a reduction in grant funding in a manner similar to Ontario’s current tuition framework.Performance funding

A variety of configurations, metrics and structures for performance funding were suggested throughout the consultation. Participants suggested funding could be competitive, with shares based on institutional performance. Others suggested performance funding be institution-specific, with a portion of each institution’s grant made re-earnable based on defined performance metrics. Many participants stressed that metrics should be negotiated between institutions and government in the SMA process. Some said the current quality and performance funding envelope could be split into undergraduate and graduate portions to enhance differentiation.

Alignment and Debate

You will note that the COU [Council of Ontario Universities] proposal addresses the structure of the funding model, but does not elaborate on goals for specific improvements in quality. The reason for this comes from current differentiation among Ontario universities. Different universities have different priorities.

A Re-designed Funding Model for Universities

(Toronto: Council of Ontario Universities, 2015)

Alignment

- Need for improved data and reporting: Strong perception exists that many important outcomes are not measured at all. Data on universities is not all validated, and needs to be made more comparable and accessible to government, stakeholders and the public. Reporting also needs to be streamlined to reduce duplication.

- Student success is more than academics: Funding should focus not only on academic program delivery, but on vital services that support effective learning and research environments.

- Focusing on experiential and other learning opportunities: Experiential and entrepreneurial learning, research, and social opportunities need to be offered to students to improve the student experience and future job prospects.

- Role of sessional and non-academic staff must be factored in: New funding formula must recognize the integral role of sessional and non-academic staff in supporting quality teaching, learning and research functions of a university.

- Differentiation and specialization efforts need to be enhanced: Differentiation is a powerful tool to achieve quality in the postsecondary education sector by focusing on universities' strengths and reducing duplication.

- Strategic Mandate Agreements should be a vehicle for differentiation: The SMA process could be leveraged for increasing differentiation among institutions and tying metrics to funding.

- Funding should accommodate various university circumstances: Funding for special purposes needs to be improved to support access, regional and linguistic diversity in the province, and universities' unique differences.

- Teaching and research excellence should be given equal weight: New funding formula should support core activities of universities. This includes all aspects of teaching, research and service.

- There must be fairness in funding: Funding should be allocated on a fair and equitable basis to protect against wide variations in quality and to support student success at all universities.

- Simple and transparent model benefits all: Funding model structure should be further simplified to remove archaic features and avoid redundancy. Allocation formula must be easy to understand and simple to administer.

- Funding should be predictable and stable: Mechanisms should be in place to ensure funding is stable and predictable to facilitate long-term planning. Protection may be needed for universities that face significant enrolment declines. Phased-in implementation is needed.

- Funding flexibility across programs and activities is important: Within an appropriate framework of transparency and accountability, the new funding formula should continue to allow universities to use funding flexibly to support adaptation to changing environments in which they operate.

- Addressing costs at universities is crucial: New funding formula should recognize significant cost pressures universities face, such as faculty salaries, pensions and general inflation. Cooperation and other opportunities for lowering the cost curve need to be encouraged.

Debate

- Balancing outcomes and funding: The sector is unclear on the extent of tying outcomes to funding formula. While some call for increasing performance funding, others think a new funding model should not be linked to outcomes or performance, or should at least avoid unintended consequences such as unhealthy competition and punitive elements.

- Measuring learning outcomes: Perception exists that student learning outcomes need to be improved. However, opinions are mixed on what should be measured and how, as well as how much funding should be linked to learning outcomes.

- Perceptions of quality differ across the sector: The “quality” of university education and student experience is viewed differently by sector stakeholders. While some see it as reflected in teaching and breadth of programming, others see it reflected in student services and well-maintained facilities. There is debate about how improvements in quality can be achieved through the funding formula.

- Need for increased accountability is not well understood: Debate exists on whether universities should be more accountable for public dollars. Some see the need for enhanced accountability for expenditure decisions others think increasing government oversight would interfere with university autonomy and create more instability.

- Role of enrolment in the new funding model: While there is acknowledgement that university costs correlate with size, stakeholders are uncertain to what extent enrolment-based funding should be maintained in the new formula.

- Provincial support for indirect costs of research: Some universities maintain that additional funding needs to be provided to cover research overhead costs. Others contend that universities already receive a significant level of funding to cover these costs.

- The need to adjust or reform program weighting: Some said it would be important to change funding by basic income unit and per student, while others said institutions have learned how to budget with their current rates.

For more perspective, see Appendix A: What Else Was Heard

Table of Contents / Top of Section

What We Learned

This section helps interpret how the feedback from the consultation relates to the four principles of the review. It serves to provide a base for strategic directions on the province’s approach to funding model design.

The consultation revealed a sense that students are increasingly looking for change in their teaching and learning experience at universities. Public debate often questions whether degrees, particularly at the undergraduate level, have less value than they used to. Universities are often criticized for not being attuned enough to the needs of the labour market, or more generally not sensitive to modern economic conditions. Student organizations communicated that they wanted more focus on teaching given rising tuition fees. There is also a view among policymakers that significant modernization of universities using collaborative and coordinated strategies has not yet occurred.

Effective funding model design

Despite these concerns, much of what we heard reflected a deeply felt passion for the value of Ontario's universities. Feedback reflected the differing needs of individual universities, as well as the aspirations and priorities of stakeholder groups. In sorting all of this advice, it was clear that a new funding approach would need to be well grounded and principled – namely, design should:

- Be based on data, easy to understand, and provide clear and consistent rationale for differences in funding allocations.

- Aim to ensure a reasonable degree of equity in the distribution of available government support. This does not mean equal funding, but rather that similar activities are funded at similar levels, in a transparent manner based on quantifiable factors.

- Allow for predictable allocations to enable institutions to engage in longer-range planning.

While mathematically-based, the choices made in the design of a formula are an important instrument in meeting government objectives. The objectivity, integrity and credibility of the distribution mechanism will be closely examined as it is aligned to support the government's four stated policy objectives.

Theme 1: Enhancing Quality and Improving the Overall Student Experience

Throughout the consultation, different dimensions of quality emerged. Quality in universities can be perceived from a customer satisfaction or value-for-money perspective, by the degree university research and innovation shapes and transforms knowledge, or by global reputation and rankings. However, in adopting a student-centric perspective this review focuses on the key element of the teaching and learning taking place at Ontario universities.

Larger class sizes, too little contact between students and faculty, sessional lecturers and an increasingly strained student support service environment were all examples cited to illustrate a declining quality of the student experience. The effectiveness of targeting one or more of these discrete components through the funding model was unclear. The best way to hold policymakers and universities accountable on student success is to reinforce desired results rather than prescribing what resources need to go into particular programs. Clear expectations are needed to improve student success through measures of increased retention, graduation, employment, labour market readiness, time-to-completion and student satisfaction.

While the need for the university funding model to support teaching quality was raised throughout the consultation, pinpointing the “problem” and corresponding “solution” proved difficult. At its heart, the question of enhancing the student experience came down to enhancing learning, demonstrating its value, and ensuring that this value is understood by students, families and society as a whole.

Many jurisdictions are trying to find ways to measure learning outcomes – an attempt to capture growth in cognitive abilities that should reasonably be expected to occur as a result of an undergraduate education. Problem solving, critical thinking, and communication are all higher-order thinking skills that are generally agreed to be core to an undergraduate experience, yet these are not transparently or consistently measured, assessed, or validated across the system.

Universities should emphasize measuring and improving these higher-order thinking skills rather than attempting to match all program disciplines with very specific jobs, especially in a rapidly evolving labour market. Employer groups were generally supportive of this view, but further engagement would likely be required to confirm how to best integrate their needs with the approach. Exploring learning outcomes measurement seems central to addressing the question of what “quality” means. However, there is currently no commonly accepted assessment regime, and students are not always aware of what skills they are acquiring.

The $3.5 billion operating grant is used to support both teaching and research. Given the relative size of this funding – about 40 per cent of operating revenues and 27 per cent of total revenues – it must be used in a focused and strategic way if it is to be effective in shaping behaviour towards desired institutional and system goals. It was clear from the consultations that the funding formula should support and promote the two core activities of a university – excellent teaching and learning, and world-class research. The degree to which universities decide to prioritize one activity over the other reflects a choice on the part of the institution about its mandate.

During the consultation, it became apparent that research is often seen to be the greater priority for many universities. Significant incentives for research excellence exist, including sponsored research funding and the perceived status and prestige associated with it. However, when it comes to universities' undergraduate teaching and learning activities, incentives beyond enrolment are unclear. Funding model design should be seen as an important tool to support a balanced system.

There was consensus that providing experiential learning, entrepreneurial knowledge and research opportunities would be beneficial. These approaches were seen as having high impact and would enrich the university experience for students who are not currently benefitting from them.

Theme 2: Supporting the Existing Differentiation Process

The university sector in Ontario is made up of a variety of institutions, each with their own strengths and needs. Throughout the consultation, groups of universities emerged based on like interests, mandates and communities served.

Despite a significant amount of competition in the system, these groups often spoke with similar voices. Common stances on global competitiveness, regional impact, and relative teaching/research mix surfaced. A few institutions, such as Université de Hearst and OCAD University, exist within highly specialized mandates. Even with similarities, there has been a reluctance for most universities to see themselves as part of groups as opposed to individual universities – particularly if it is perceived to limit aspirations or status.

Universities and sector partners are increasingly acknowledging the benefits of recognizing these differences with a differentiated funding policy. This was not always the case. Significant support and gains have been achieved since the ministry released its Differentiation Policy Framework for Postsecondary Education in 2013. Many participants thought that designing a funding formula to recognize the strengths, contributions, and aspirations of individual universities was both possible and necessary.

It is clear that the Strategic Mandate Agreements are seen as the best vehicle for negotiating any funding tied to differentiation. Many ideas have emerged. Linking funding to common metrics with targets that would be negotiated separately by each university was one. Introducing a re-earnable portion of current funding levels to negotiated metrics was another. Others indicated that funding tied to metrics specific to groups of universities with different types of weightings would be a more viable approach.

Theme 3: Improving Transparency and Accountability

Transparency is a key element of maintaining public support. It promotes openness, communication, and accountability.

As a first step, progress must be made on cleaning-up the current model. While consensus emerged for some changes – eliminating archaic and unused elements, streamlining the Basic Operating Grant – other ideas were much more controversial. Proposals to address per-student funding anomalies between universities and examine the accuracy of program weights were received warily. They were seen as funding shifts from one university to another that should not be attempted in times of financial restraint, making transparent the reasons different universities receive differing amounts of money should be a core feature of any funding model.

Informed decisions require accurate and available data. There is a large amount of data that is currently made available, but it is not all transparent, validated or made relevant to the public. Increased transparency in key metrics may be enough to advance some policy goals. Central data collection by government would be an important step.

The lack of coherent data further limits the range of options available for funding formula reform and the ability of the system to measure results. The ministry and the sector must have the tools necessary to demonstrate accountability on system goals and to advance funding model design, and universities must be assured of a structured and inclusive process to data collection. Several stakeholders raised concerns over the ministry's ability and current capacity to undertake this task. In a review of other funding models used across the broader public sector, long-term data strategies have yielded impressive results.

The degree to which the ministry can resolve some issues facing universities is limited due to the governance relationship. While some broader public sector entities are financially consolidated and directly regulated, others operate with a high level of independence, with funding being an essential influencing tool. Universities operate in an environment of legal and cultural autonomy. Governed by individual legislative mandates, universities bargain individually and sponsor a variety of pension plans. Most universities also have unique bicameral governance structures that separate academic and financial oversight.

Theme 4: Addressing Financial Sustainability

Universities are increasingly managing their operating budgets through enrolment growth, economies of scale and teaching efficiencies. These methods disproportionately impact students, and they cannot be maintained indefinitely. Although outside the scope of the review, faculty renewal, pension reform and administrative efficiencies were often cited as necessary steps.

The current funding model will make institutions with declining enrolments vulnerable. Reallocating funds alone may not fully address their challenges. The funding model, in supporting differentiation, can help universities continue to focus on their strengths, reduce unnecessary duplication and reward the achievement of a variety of outcomes. The model should be designed to help universities realize an optimal size, unique mission and longer-term sustainability.

A new planning partnership is needed – coupled with a strengthened stewardship role for the ministry. Improvements can be made through enrolment planning, financial health measurement and monitoring, and cost benchmarking as a productivity measure. In meeting with the chairs of university boards of governors, it became apparent that there was a demand for this kind of information at senior levels of university leadership.

The new funding model should introduce a proportion of funding that is based on outcomes – funding that is at risk and earned only through successful performance based on metrics expressed in each university’s Strategic Mandate Agreement (SMA). . . . This performance-based fund should comprise a reasonable proportion of operating grants at the outset of implementation. The proportion of performance-based funding should grow over time with new investments, as government and universities gain experience and understand impacts.

A Re-designed Funding Model for Universities

(Toronto: Council of Ontario Universities, 2015).

Table of Contents / Top of Section

Strategic Directions: Focus on Outcomes, Centre on Students

Change to the university funding model should be focused on improving outcomes, with an emphasis on the government's objective of improving the overall student experience. While it is difficult to imagine a funding formula entirely divorced from enrolment, new measures of success must be included. Simply put, there is a need to establish a direct connection between public funding and the educational needs, goals and priorities articulated by the province.

The basics

- The ministry should apply an outcomes lens to all of its investments. Clarity about the objectives the ministry wishes to meet through the outcomes-based funding will be crucial. The outcomes lens should start with a focus on undergraduate student success – this work can start immediately.

- The success of an outcomes-based approach depends on valid and reliable data; strong, credible metrics; and the capacity to measure identified outcomes. The ministry would be responsible for ensuring data is coherent, centralized and easily accessible to the public. An extended debate on methodologies or technical aspects will not be useful. A third party may need to settle debate on data and measurement definitions to get resolution quickly. To ensure success, substantial statistical expertise of the third party will be critical.

- The ministry should introduce an outcomes-based component of funding that could grow over time. While some funds are currently allocated based on key performance indicators, the proportion is too small to reinforce a culture of continuous improvement.

- Full implementation should occur over two Strategic Mandate Agreement cycles, with the first elements put in place in time for the 2017 negotiations. As the current “data state” limits the number of feasible funding model options, implementation planning has to extend to future agreement negotiations. This will allow for alignment with the end of the current tuition policy framework, and the results of the review of the college funding formula.

Champion and implement the assessment of learning outcomes

Understanding what students know – and what they should know – as a result of their time at university is critical to addressing quality. Measuring and assessing undergraduate learning outcomes has the potential to add considerable value to the sector, helping students to understand what they have learned, governments to understand what skills are being generated, and universities to drive continuous improvement. It is for these reasons that previous recommendations to the Ontario government have identified such assessment as important to determining the value added through education.1

- Current work on learning outcomes should be accelerated.

- In an ideal end state, measuring and assessing learning outcomes should be a priority for institutions and a condition of funding.

Fulfil the ministry's stewardship role

The ministry refers to itself as a “steward” in its Differentiation Policy Framework for Postsecondary Education (2013), and continues to work with the sector on this evolving concept. What that means with respect to the funding relationship is not yet well defined.

- Ongoing engagement with the sector during the funding reform process would be an excellent way of demonstrating the evolving stewardship role.

- Once specifics of an outcomes lens is developed, the ministry should leverage the SMA process by linking the two with a public reporting mechanism.

- The ministry should continue using the Strategic Mandate Agreements to help each institution achieve further differentiation, reinforce the outcomes-based perspective and accommodate similar group interests – namely those of specialized, comprehensive, regional or research-intensive universities.

- The ministry should strengthen its enrolment planning role in light of demographic changes, regional needs and institutional strengths.

- Institutional financial health monitoring and cost benchmarking are other areas where the ministry could explore strengthened stewardship.

Striking a good balance between ministry oversight and institutional autonomy should be part of the evolving conversation on stewardship. The role of the ministry is to set the stage for universities – it cannot manage the system and must stand aside to let the system experiment. A track record of good performance can be rewarded with more flexibility for some universities, while clear conditions should be maintained when the ministry does act.

Modernize Ontario's funding methodology

Ontario's current funding model has evolved over time, now representing decades of decision-making that is no longer well understood.

- Outcomes-based funding that grows overtime should be phased in.

- Outdated historical grant elements should be eliminated;2 progress on addressing funding per-student anomalies should be made; and separate envelopes for areas requiring different policy treatment should be created – possibly undergraduate, graduate and managed enrolments such as teaching and medical.

- Special purpose grants related to institutional circumstances – namely size, geography or specialization – should be consolidated into one envelope with a valid methodology.

- The ministry should consolidate many student-centric special purpose grants into a common “student priorities” envelope. While the ministry needs to pilot new ideas, once change has been achieved, a way of transitioning best practices into ongoing funding is needed.

- The ministry should work with universities to develop a better understanding of program costs – either to replace the current approach to weighted enrolment funding with a simplified model, or to validate it.

- Enrolment should still be part of the model. For universities facing declining enrolments, the ministry should introduce a support mechanism with defined conditions as well as some way of stabilizing finances.

What about research?

Research is a central part of a university's activities. Currently, the ministry operating grants to universities appear to be shifted to subsidize the administrative costs of research, but it is unclear whether the province should prioritize this activity through the funding model. The ministry has an important role to play in supporting universities as they find the right balance between their teaching and research agendas.

- The ministry has a role in monitoring the financial health of universities, including the increasing financial impact of research intensiveness. In collaboration with other provincial and federal government bodies, the ministry should work with universities to explore the increasing impact of indirect and direct sponsored research costs.3

- As a part of the Strategic Mandate Agreement process, the ministry should continue to ensure that graduate activity is appropriately focused in established areas of research excellence or intensity.

- Institutional resources dedicated to teaching and research should be monitored, probably by tracking teaching loads or research activity.

- After focusing on student success as a starting point, the ministry’s outcomes lens should be extended to include research excellence.

While priority in a new funding model should be given to reinforcing a student-centric perspective, the ministry operating grant will also support research activities. It should also be noted that the Auditor General of Ontario recently released a report on university intellectual property and research funding.4

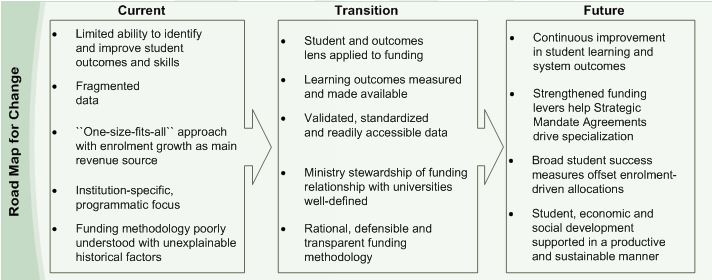

A Road Map for Change

There are a number of paths the ministry could take when reforming the existing university funding formula. Setting a vision and articulating clear objectives is essential to success. One potential route is pictured below.

The transition between the current and future states requires significant work. Workable targets and goals must be set and resources will need to be allocated against the strategy. Substantial time will be needed to implement changes, requiring collaboration between the ministry and universities. At the same time, some work will need to be prioritized early on. The ministry must ensure that the systems and procedures are in place for stakeholders to be involved in finding solutions.

Table of Contents / Top of Section

Further Observations

Outside of the scope of this review, but linked to the themes of this report, are the following observations:

- Impact on colleges of university funding reform

In 2014, the ministry committed to reviewing the funding formulas for universities and colleges, starting with universities. Colleges are increasingly vulnerable to regional demographics and increased competition for students. Consulting both sectors on joint areas of interest is advised.

- Faculty renewal, pension reform and inflation