Chapter 1 – A closer look at student outcomes

Section I – Alignment with student needs: Evidence from the college sector

Introduction

In this section, we present an analysis of the extent to which college credentials are aligned with student needs using graduation data from the Ministry and labour market data from the College Graduate Survey for the period 1999-2013, the Labour Force Survey for the period 2009-2013, and from the National Household Survey, 2011. Table 4 describes each indicator.

| Graduate outcome indicator | Measure | Data source | Time of collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Graduation | Among all students who enroll in a program, the percentage that graduate from it within a given time frame. Graduation rates are calculated 7 years after enrolment for 4-year programs and 200% of the typical program duration for other programs.8 | Ministry KPI data | Colleges collect graduation rates at the end of the completion timeframe and they are reported to MTCU one year later |

| 2. Earnings | Total annual earnings before tax deductions and transfers among employed graduates. Inflation-adjusted with the Consumer Price Index for Ontario. Indexed at 2010=100 | GOSS – Self-reported gross annual earnings at time of survey | 6 months post-graduation Age 22-29 (2009-2013) |

| LFS – Annual earnings derived from self-reported wage | Age 22-29 (2009-2013) | ||

| Synthetic, cumulative earnings age 25-64 | NHS – Self-reported annual employment earnings from 2010 | 2011 (reference period is 2010) | |

| 3. Unemployment rate | Among graduates in the labour force, the percentage who are unemployed | GOSS – Self-reported employment status at time of survey | 6 months post-graduation |

| LFS – The percentage of labour market participants who are not currently employed at time of survey | Age 22-29 (2009-2013) | ||

| 4. Labour force participation rate | Among all graduates, the percentage who are either employed or looking for employment | GOSS – Self-report of being either employed or seeking employment at time of survey | 6 months post-graduation |

| 5. Returned to education | Among all graduates, the percentage that returned to education within six months of graduation | GOSS – Self-report of being enrolled in post-secondary education at time of survey | 6 months post-graduation |

| 6. Employed in related field | Among employed graduates, the percentage who are working in a field related to their postsecondary education | GOSS – Self-report of employed graduates working in a “job related to the program that [they] graduated from?” at time of survey. | 6 months post-graduation |

| 7. Work preparation satisfaction | Among employed graduates, the percentage who are satisfied with their college preparation for the type of work they are doing | GOSS – Graduate rating of “Satisfied” or “Very satisfied” with their college preparation for the type of work they are doing | 6 months post-graduation |

| 8. Achieved post-secondary goals satisfaction | Among all graduates, the percentage who report that their college education was useful in achieving their post-graduation goals | GOSS – Graduate rating of “Satisfied” or “Very satisfied” with the usefulness of their college education in achieving their post-graduation goals | 6 months post-graduation |

| 9. Would recommend the program | Among all graduates, the percentage who report that they would recommend their program to someone else | GOSS – Graduate answer of “Yes” to question: Would you recommend the (program name) to someone else or not? | 6 months post-graduation |

Field of study and credential outcomes

The importance of field of study

Before discussing outcomes, we begin with a brief discussion of the importance of field of study. Field of study (FOS) is an important factor in understanding differences in outcomes both across credentials and over time within credentials. In this section we illustrate three key points:

- FOS composition varies considerably across credentials.

- FOS composition varies considerably over time within credentials.

- Both types of FOS variation are important factors in understanding across-credential differences in labour-market outcomes and changes over time in these differences.

Understanding this relationship is important since it inevitably complicates the estimation of credential effects. For ease of presentation at this point in the chapter, we restrict our discussion to occupational divisions. As we move to a more detailed discussion of credential outcomes, we also move to a more detailed discussion of FOS. (See Box 1 for an overview of how FOS is captured in the GOSS data.)

The relationship between field of study and earnings

We start with a simple illustration of the relationship between FOS and earnings. Table 5 shows the mean earnings of graduates of programs in different occupational divisions over the 2009-2013 period. As Table 5 shows, Health graduates earn the most, followed by Technology, Business, and Applied Arts graduates. Of course, as we will see later in the chapter, part of these earnings differences is attributable to differences in the credential distribution for each occupational division, but most of the differences remain conditional on credential. These earnings differences associated with FOS are likely important if FOS varies across credentials. In other words, earnings outcomes associated with a credential may be largely driven by which fields are most common within the credential.

| Occupational division | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|

| Applied Arts | $25,551 | $28,420 |

| Business | $27,028 | $30,620 |

| Health | $32,786 | $38,213 |

| Technology | $31,806 | $35,280 |

The percentage of graduates in each division by credential over time

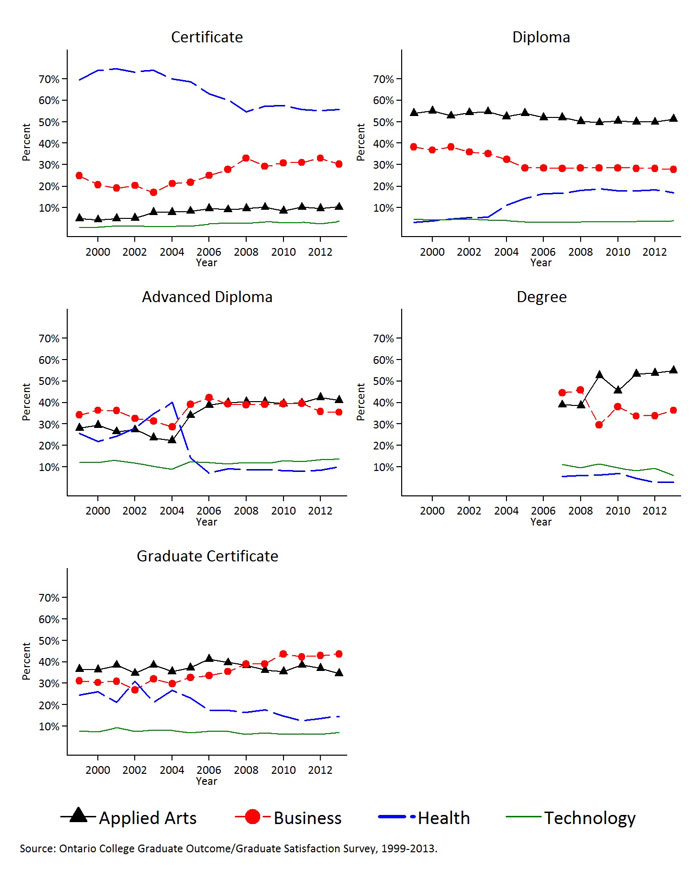

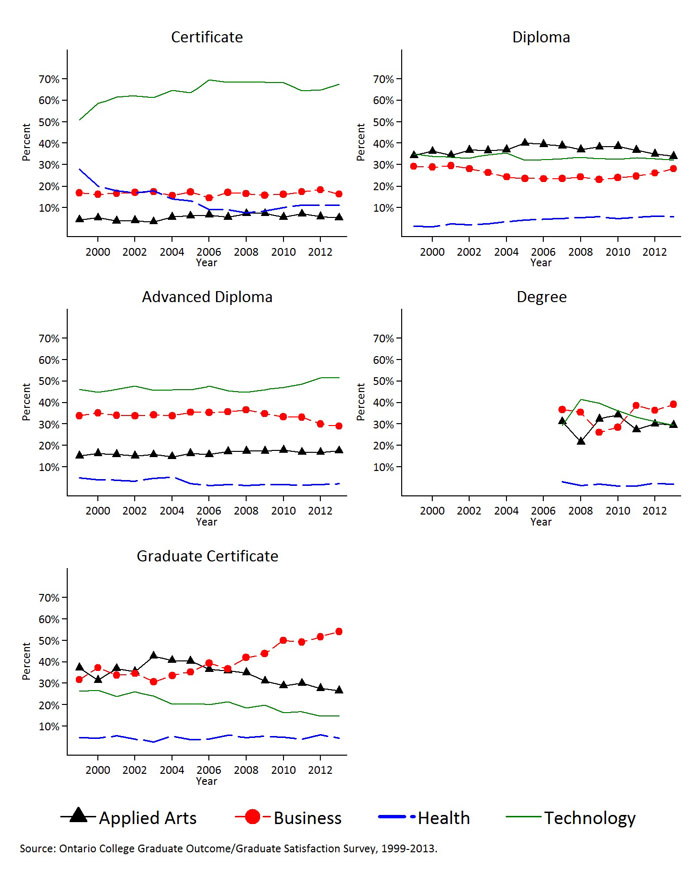

Next we turn to a discussion of the percentage of graduates in each occupational division for each credential. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate how the field of study (FOS) composition has changed over time for each college credential. As Figures 1 and 2 show, FOS varies considerably across credentials and FOS varies considerably over time within credentials. This variation is especially striking for females. We highlight three examples:

- Female certificate graduates – For female certificate graduates, the most popular occupational division by far is Health and this is consistent over the entire time period. However, the percentage of certificates in the Health occupational division has been declining sharply and the percentage of Applied Arts and Business certificates has been increasing.

- Female diploma graduates – Before 2004, most female diploma graduates were in Applied Arts or Business, with almost none in Health or Technology. After 2003, the percentage of female graduates in Health began to steadily rise, as the percentage of Business graduates decreased correspondingly. During this period, the percentage of Applied Arts and Technology graduates remained largely unchanged.

- Female advanced diploma graduates – Before 2004, female advanced diploma graduates were somewhat evenly distributed across Applied Arts, Business, and Health occupational divisions. However, after 2004, there is a sharp drop in the percentage of female advanced diploma graduates in the Health occupational division. (This is largely explained by the shift from Nursing as an advanced diploma program to Nursing as a collaborative degree program.9) After this point, there is a slight increase in the percentage of female advanced diploma graduates in the Applied Arts and Business divisions.

Figure 1: Percentage of female college graduates, by occupational division, GOSS 1999-2013

Figure 2: Percentage of male college graduates, by occupational division, GOSS, 1999-2013

Indicator 1: Graduation rates

Graduation rates – trends

Graduation rates vary by credential and length of program

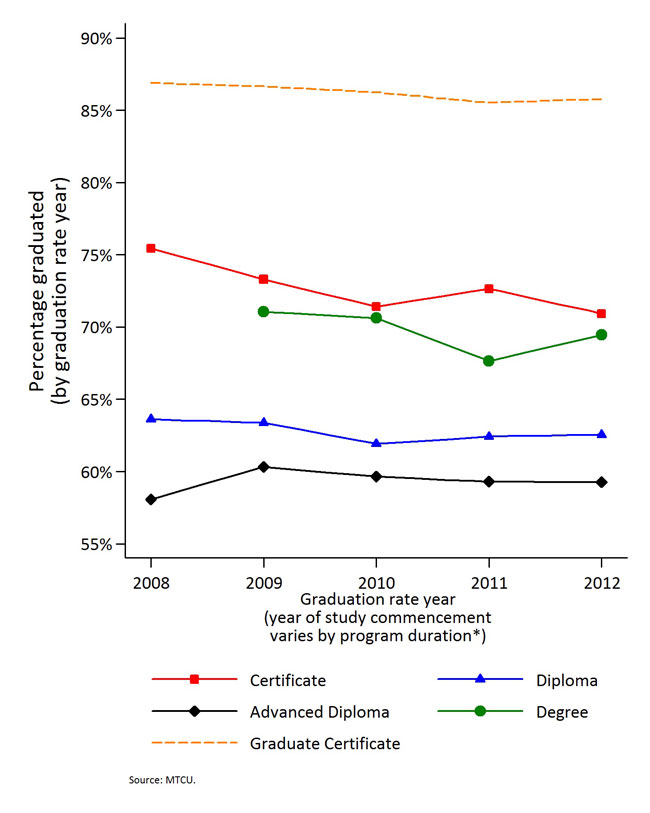

Figure 3 presents a time series of graduation rates for male and female students. Caution should be taken when interpreting trends in graduation data due to the nature of the graduation rate KPI. The number of years between the commencement of a student's studies and their inclusion in the graduation rate varies depending on the student's credential. As a result, for a given year the graduation rate for shorter credentials is based on graduation outcomes of students who started their studies much more recently than students from longer credentials.

As indicated in Figure 3, graduation rates tend to be higher for credentials with shorter time commitments, with the notable exception of degrees. Graduation rates are highest for graduate certificate students by a large margin, followed by certificate students, degree students, diploma students and advanced diploma students. In general, these graduation rates follow the order of program length, with the exception of degree students, who have a higher graduation rate than those enrolled in shorter programs for diploma and advanced diploma credentials.

The gaps between the graduation rates of different credentials generally persist over time, except for a temporary widening of the graduation gap between certificate students and degree students in 2011. Graduation rates are stable for most credentials. The graduation rate for certificate students declined between 2008 and 2012; applied degree students experienced a decline in 2011, but rebounded in 2012.

Graduation rates vary by occupational division across and within credentials

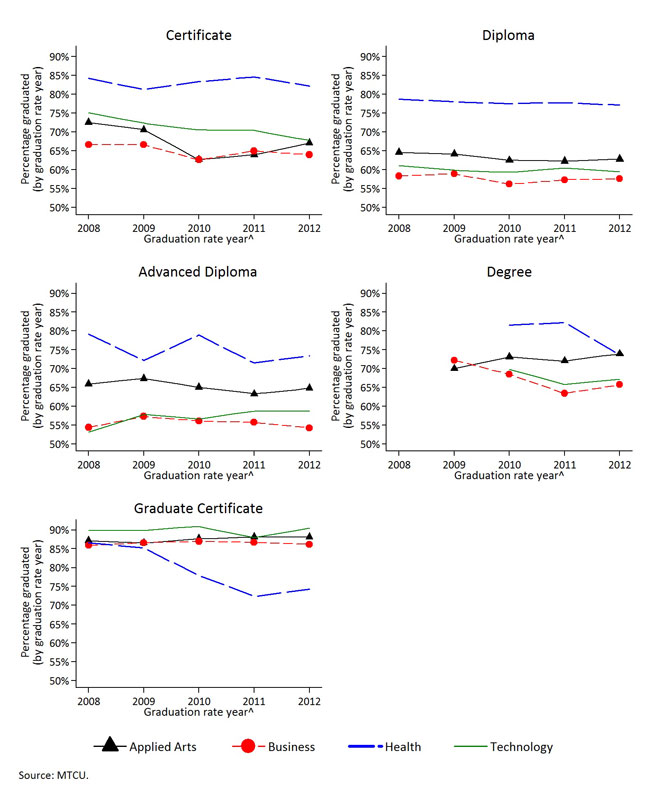

Figure 4 presents time series of graduation rates for male and female students across occupational divisions, for each credential.

For diploma, advanced diploma, and degree students, graduation rates follow a similar overall pattern. With the exception of degree graduation rates in 2012, students in Health programs tend to have much higher graduation rates than other occupational divisions within these three credentials, followed by Applied Arts students, then Technology students with marginally higher graduation rates than Business students. Graduation rates for certificate students show a similar pattern; however, graduation rates of certificate students in Technology programs are higher than those of Applied Arts and Business students. Finally, graduation rates for graduate certificate students do not vary substantially by occupational division, except for considerably lower graduation rates for graduate certificate students in Health programs starting in 2010.

No strong trends are visible for any occupational division as a whole; however, changes over time are visible within specific credentials. Graduation rates for graduate certificate programs in Health declined from 85.2% in 2009 to 72.4% in 2011. For degree programs in Health, graduation rates declined from 82.2% in 2011 to 73.7% in 2012. Graduation rates of certificate students in Technology programs decreased from 75.2% in 2008 to 67.8% in 2012.

Figure 3: Ontario college graduation rates by credential for KPI, Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities, 2008-2012*

* Graduation Rates indicated for KPI Reporting Year. Commencing 2000-01, Graduation Rates are based on tracking individual students, where, for example, the 2013-14 KPI Graduation Rate is based on students who started one-year programs in 2011-12, two-year programs in 2009-10 three-year programs in 2007-08 and four-year programs in 2006-07, and who had graduated by 2012-13. KPI Graduation Rates include changes resulting from the KPI Review and Adjustment process (where required).

Figure 4: Ontario college graduation rates by credential and occupational division Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities, 2008-2012^

^ Graduation Rates indicated for KPI Reporting Year. Commencing 2000-01, Graduation Rates are based on tracking individual students, where, for example, the 2013-14 KPI Graduation Rate is based on students who started one-year programs in 2011-12, two-year programs in 2009-10 three-year programs in 2007-08 and four-year programs in 2006-07, and who had graduated by 2012-13. KPI Graduation Rates include changes resulting from the KPI Review and Adjustment process (where required).

Indicator 2: Earnings

Earnings – trends

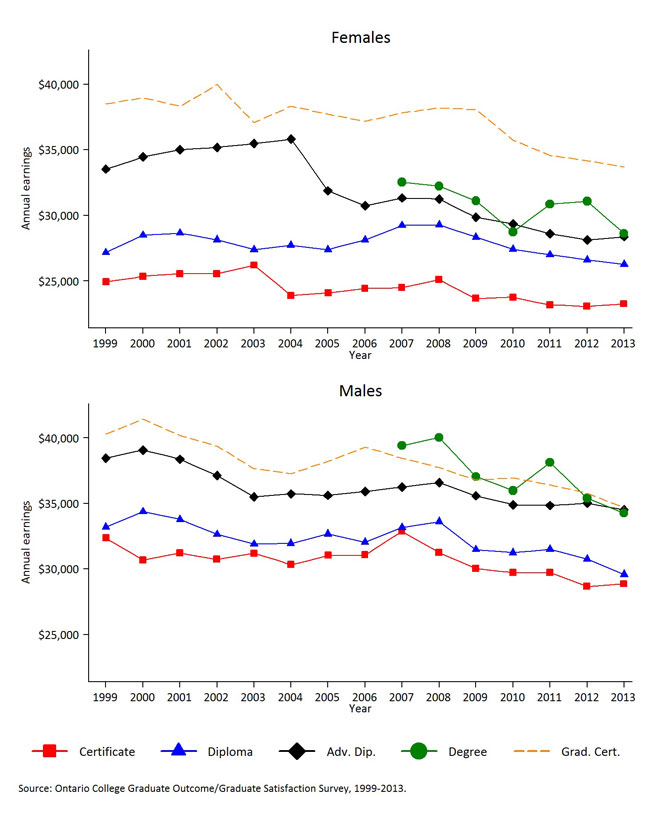

Figure 5 presents time series of mean annual earnings for employed male and female graduates who responded to the survey and with non-missing earnings responses (the handful of graduates who reported zero annual earnings were excluded). Earnings are indexed at 2010=100 with the Ontario CPI.

Higher credentials are associated with higher earnings

As Figure 5 illustrates, graduates with more advanced credentials had higher mean earnings. The gaps are sizable, with mean annual earnings between adjacent credentials generally being several thousand dollars. The gaps change in magnitude but generally persist over time, with the exception of earnings at the end of the time series. Earnings of male certificate and diploma graduates converge at the end of the time series, as do earnings of male advanced diploma, degree, and graduate certificate graduates. Earnings of female degree and advanced diploma graduates also converge at the end of the time series.

Substantial gender differences exist within each credential. Male graduates earn substantially more than female graduates across credentials, with the exception graduate certificate graduates, who experience roughly equal earnings across genders.

Earnings declined over time for all credentials

As Figure 5 also shows, real earnings declined over time for all credentials. Overall, these declines are not large; however, they were larger for more advanced credentials, particularly for advanced diplomas, degree programs and graduate certificates. Female advanced diploma graduates experienced a significant drop in earnings in 2005. This drop coincided with a substantial drop in the percentage of female advanced diploma graduates in health-related programs. This change in FOS was driven by a policy change related to Nursing and explains virtually all of the earnings decline associated with advanced diplomas for women.

More broadly, while part of the overall decline in earnings of college graduates may be due to changing earnings premiums associated with each credential type, it is important to understand these longer-term structural trends in the context of short-term business cycle effects. As Figure 5 shows, much of the decline in earnings occurs from 2008 to 2010, in line with the timing of the global financial crisis and subsequent recession. This decline is consistent with the broader decline in earnings across the labour force (not just for recent graduates). Therefore, the earnings results presented in this chapter should be interpreted not simply as trends in earnings capacity associated with achieving these credentials, but also as a reflection of the reactivity of those earning these credentials to unfavourable macroeconomic and labour market conditions.

Figure 5: Mean annual earnings of college graduates, by credential and gender, GOSS, 1999-2013

Earnings and field of study

Measuring education's relationship with earnings

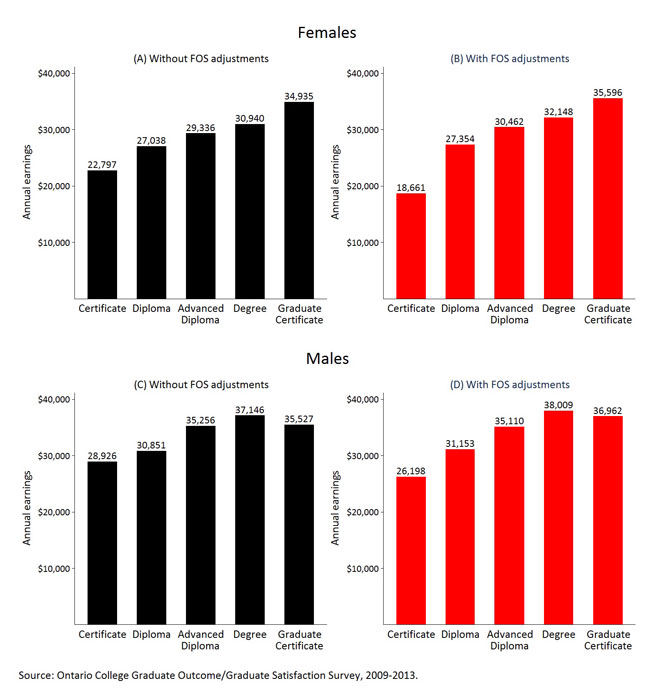

We now build on the descriptive results in Figure 6 and present results from regression analyses. Data are pooled for the years 2009-2013. Pooling this more recent subset of survey years ignores trends in earnings over time; however, it provides some analytical clarity when considering the role of field of study in relation to graduate outcomes.10 Through regression, we can calculate adjusted mean earnings for each credential that control for factors that vary across credentials, such as graduates' age and the region of the granting institution, both of which likely influence earnings.

Panel A of Figure 6 presents mean annual earnings for females that have been adjusted for age and region of granting institution. Consistent with the trends discussed above, earnings are higher for more advanced programs, as expected, given the more advanced skills developed in these programs. Panel B of Figure 6 presents mean earnings of female graduates with FOS adjustments.

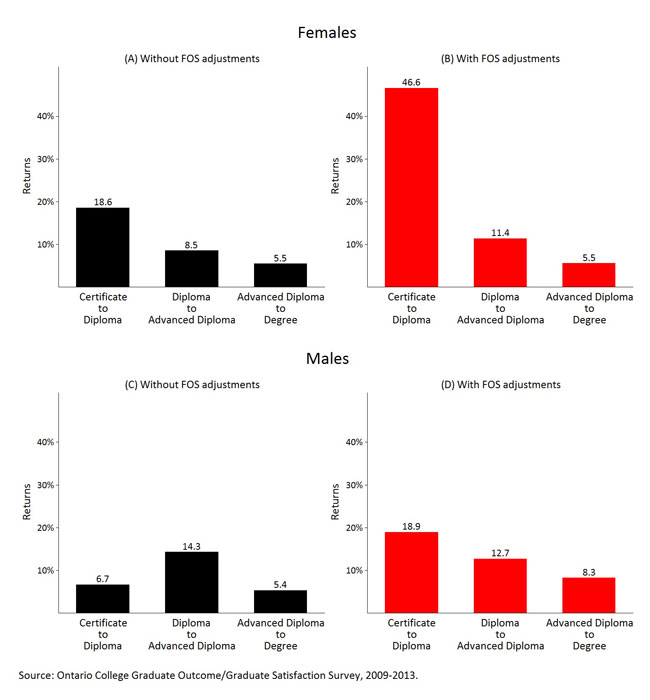

Education's relationship with earnings is often characterized with an “earnings premium”, which is the ratio of the mean earnings of the graduates of a higher education level divided by the mean earnings of the graduates of a lower education level. Drawing on the values in Figure 6 the earnings premium for a diploma relative to a certificate for female graduates is $27,038/$22,797 = 1.186. The effects of education are also often reported as “returns to education”, which are earnings premiums expressed as a rate of return. For example, the returns to a diploma relative to a certificate are 18.6%

[(1.186 – 1) × 100% = 18.6%]. This value is presented graphically in Figure 7.

Returns are usually calculated by comparing one credential to another credential representing a lower level of investment. When calculated for a one-step increase in investment, these are “marginal returns”. We use the mean earnings presented in Figure 6 to also calculate returns for the comparison of certificates to diplomas, diplomas to advanced diplomas and advanced diplomas to degrees. (Returns to graduate certificates are not calculated because it is unclear what they should be compared to, since we do not know the education status of students prior to completing the graduate certificate.) The resulting three marginal returns estimates (Figure 7) vary dramatically, even though each represents a comparison of credentials that are one year apart in duration and the longer program in each case is designed to be more advanced. The marginal returns to diplomas for female graduates (18.6%) far exceed returns to advanced diplomas (8.5%), which far exceed returns to degrees (5.5%). For male graduates, the marginal returns of advanced diplomas (14.3%) are considerably larger than the marginal returns to diplomas (6.7%), while the lowest marginal returns are associated with degrees (5.4%).

Adjusting for field of study greatly affects marginal returns estimates

FOS may help us further understand earnings differences across credentials. We adjust for FOS differences by adding indicator variables for occupational cluster to the regression models used to generate Figures 6 and 7. The basic idea is to make adjustments and estimate mean earnings under the counterfactual scenario where each credential has the same FOS distribution as the entire group of graduates. So, if a credential had a higher proportion of graduates from Health programs than other credentials, our adjusted model would estimate what the earnings of graduates from this credential would be if it instead had the same proportion of graduates from Health programs as the average of all college credentials. We do this adjustment at the occupational cluster level instead of occupational division because it has more categories, allowing us to better address across-credential FOS differences.

FOS-adjusted mean earnings for females are presented in Panel B of Figure 6. The most striking difference is the over $4,100 drop in the earnings of certificate graduates (from $22,797 to $18,661). This large decline is owing primarily to the high proportion of Health graduates among female certificate graduates. Thus certificate graduates' earnings may seem low compared to the other credentials, but their earnings are actually helped by what we could call their “advantageous FOS distribution”. The FOS-adjusted earnings of diploma graduates are largely unchanged, which is unsurprising because they are by far the largest group, so their FOS distribution closely resembles the overall FOS distribution. Therefore, the counterfactual condition closely resembles the actual condition.

We can calculate FOS-adjusted marginal returns with the FOS-adjusted mean earnings. FOS adjustments have more than doubled the marginal returns for females to a diploma (Panel B of Figure 7) because adjustments greatly lowered female certificate graduates’ earnings, which both widened the certificate-diploma earnings gap and reduced the denominator for the returns calculation. FOS adjustments increased the earnings of female advanced diploma graduates by over $1,100 (from $29,336 to $30,462), increased the earnings of degree graduates by over $1,200 (from $30,940 to $32,148) and increased the earnings of graduate certificate graduates by over $600 (from $34,935 to $35,596). The adjusted means increased the marginal returns to advanced diplomas for females, though more modestly, from 8.5% to 11.4%. Adjusting for FOS had no effect for returns to degrees for females.

Next we turn to male earnings adjusted for age and region (Figure 6, Panel C). Predictably, male earnings exceed female earnings for each credential. Marginal returns (Figure 7, Panel C) for males are quite different than for females (Panel A). For males, marginal returns are highest for advanced diplomas, whereas among females, advanced diplomas had the lowest marginal returns; marginal returns are lower for degrees for males than they are for females; and marginal returns are roughly equal for degrees across genders. FOS-adjustments for males (Figure 6, Panel D) lower the earnings of certificate graduates by over $2,700 (from $28,926 to $26,198), increase diploma graduate earnings by about $300 (from $30,851 to $31,153), lower the earnings of advanced diploma graduates by roughly $150 (from $35,256 to $35,110), increased the earnings of degree graduates by over $800 (from $37,146 to $38,009), and increased the earnings of graduate certificates graduates by over $1,400 (from $35,527 to $36,962). FOS adjustments greatly increased the returns for males to diplomas and made the marginal returns across different credentials more equal.

Figure 6: Mean annual earnings of college graduates, by credential and gender, GOSS, 2009-2013 (pooled)

Figure 7: Marginal returns for college graduates, by credential and gender, GOSS, 2009-2013 (pooled)

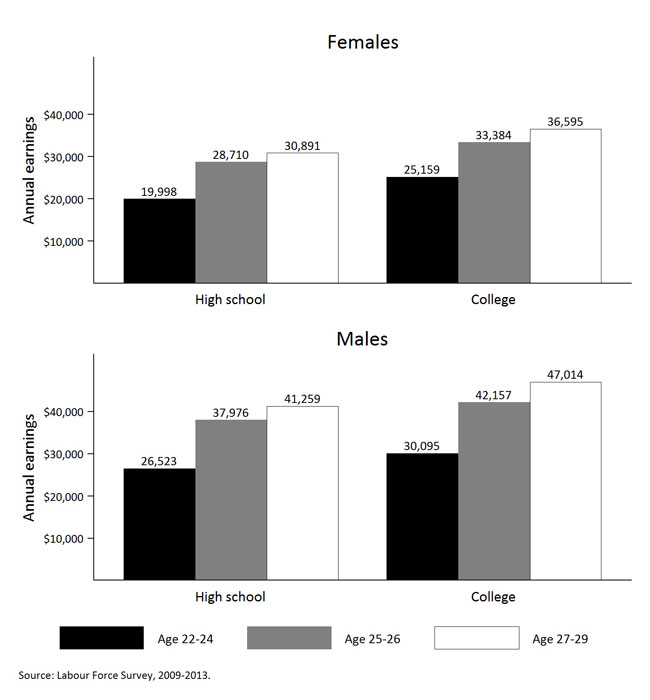

Earnings improve substantially as graduates gain labour market experience

Outcomes in the GOSS are for six months after graduation, but it would be useful to understand outcomes further after graduation. Figure 8 presents earnings data across age groups from the Labour Force Survey (LFS). The results suggest that earnings for college graduates increase substantially as they gain labour market experience. For female college graduates, annual earnings at age 27-29 are 45% higher than earnings at age 22-24. For males, college graduate earnings increase by 56% across these age ranges.

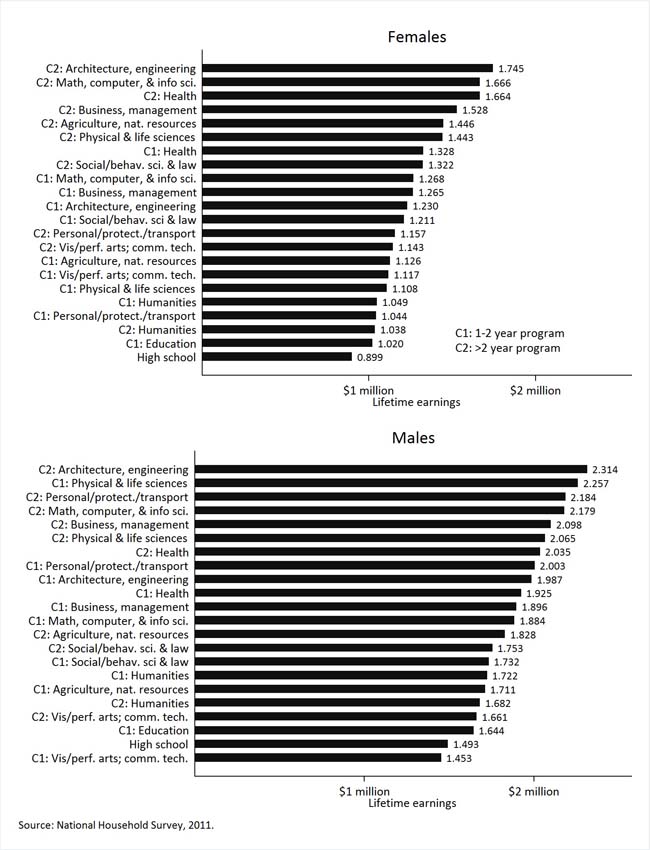

Lifetime earnings vary widely across credential level and field of study, but graduates of almost all college programs have higher lifetime earnings than high school graduates

Education's effects can also be understood in terms of lifetime earnings, conventionally measured as the total earnings over the course of one's working life.

Few data sets measure earnings over individuals' entire working lives, so most lifetime earnings research use synthetic lifetime earnings, which are constructed by summing the mean earnings of people with the same characteristics who are at different ages. Using the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS), we calculated lifetime earnings for ages 25-64, by the credential levels and fields of study available in the NHS. Synthetic lifetime earnings are not expected to accurately forecast recent graduates' lifetime earnings, which could differ substantially from past graduates. However, they provide a useful summary measure of labour market outcomes and a foundation upon which such forecasts could be based.

Figure 9 presents lifetime earnings across credential level and FOS, with C1 indicating 1-2 year college programs, and C2 indicating >2 year college programs. Lifetime earnings vary greatly across credential level and FOS, but graduates of all program types in the NHS have higher mean lifetime earnings than high school graduates of the same gender, except male graduates of short college programs in Visual and Performing Arts. Many college programs — especially longer programs in Health, Sciences, Technology and Business – have strong lifetime earnings.

Figure 8: Mean annual earnings in Ontario by age group, educational attainment and gender, LFS, 2009-2013 (pooled)

Figure 9: Synthetic lifetime earnings of Ontario college graduates, NHS, 2011

Indicator 3: Unemployment

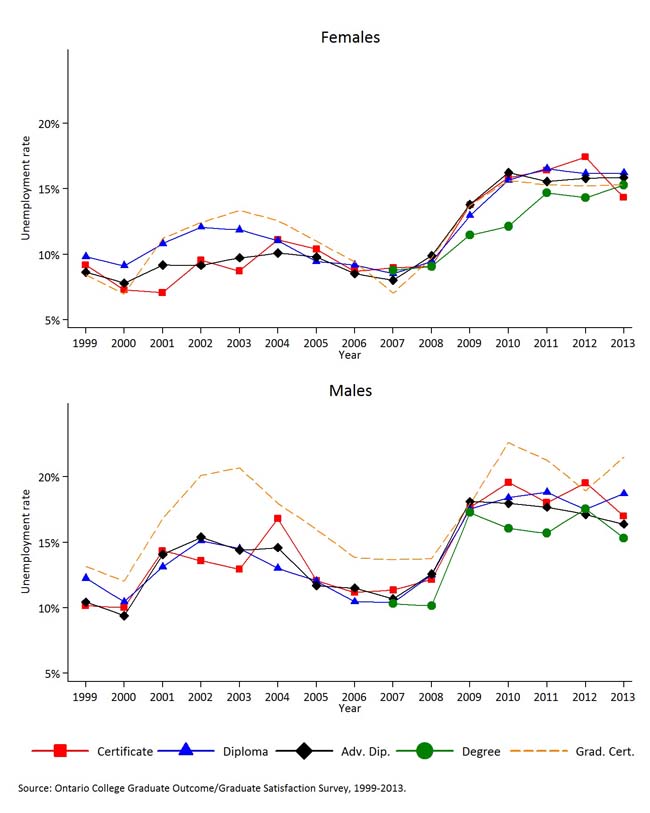

Unemployment rates lower for more advanced college credentials

Figure 10 presents trends in unemployment rates for male and female graduates six months after graduation, by credential. Graduates are considered unemployed if they are not full-time students, are not employed, and are either looking for work or have accepted a job expected to start shortly. The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed divided by the total number of graduates in the labour force, again excluding full-time students. The impact of a strong labour market in the early 2000s and a weak labour market beginning in 2009 are clearly evident. Also evident are temporal fluctuations in unemployment differences across credentials. These two observations may be related, because across-credential differences appear to grow during recessions. This is most notable for graduate certificates among males, where unemployment is very high during periods of weak economic activity. Whatever their cause, temporal fluctuations make summary statements of unemployment differences across credentials difficult. However, in recent years a general pattern has emerged of lower unemployment rates for graduates of more advanced credentials, with degree and advanced diploma graduates experiencing generally lower unemployment rates than graduates of certificate and diploma programs.

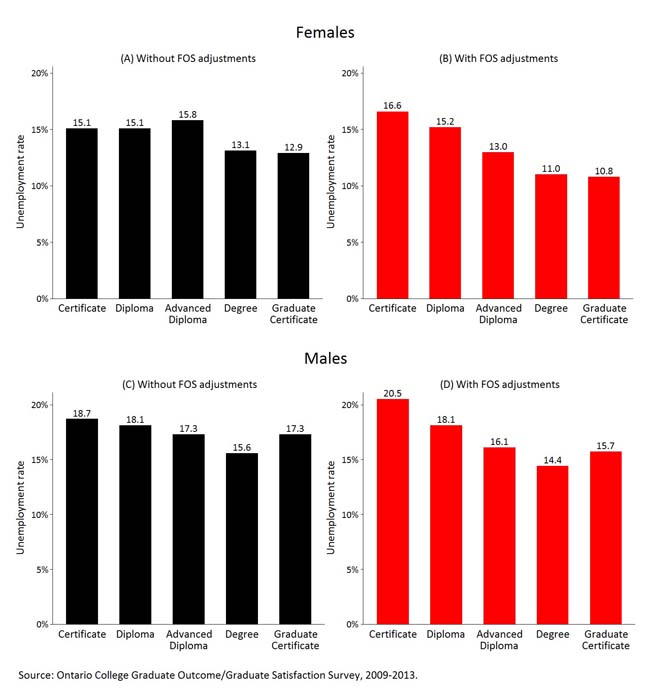

Controlling for field of study magnifies differences in unemployment rates across credentials

Next we focus on the 2009-2013 period to highlight recent differences across credentials. Figure 11 presents the unemployment rate for graduates of each credential. In this model, we account for differences across region and age by setting the region and age distributions for each credential to the overall distribution for all credentials in this period. Panel A shows important unemployment differences across credentials for female graduates.

Female certificate and diploma graduates experience high unemployment rates, at 15.1% for both credentials. Unemployment rates are higher for female advanced diploma graduates, at 15.8%. Across genders, unemployment rates are lowest for degree and graduate certificate graduates. Based on these results, we see a general pattern in which more advanced credentials have lower unemployment, with the exception of advanced diplomas.

Panel B presents unemployment rates for females under the counterfactual condition that the FOS distribution for each credential is the overall FOS distribution for all female college graduates. Unemployment rates for female diploma graduates remain virtually unchanged, but the FOS adjustment made important changes to the unemployment rates for female graduates of other credentials. The unemployment rate increased 1.5 percentage points for female certificate graduates (from 15.1% to 16.6%), decreased 2.8 percentage points for female advanced diploma graduates (from 15.8% to 13.0%), and decreased 2.1 percentage points for female degree and graduate certificate graduates, respectively (13.1% to 11.0%, and 12.9% to 10.8%). As Panel B shows, once we adjust for FOS, we see a clearer pattern in which more advanced credentials have lower unemployment rates.

Panel C presents unemployment rates for males. Consistent with the earlier time plots, a comparison by credential of Panels A and C (female and male unadjusted unemployment rates) shows that unemployment is higher for males at every credential.

For males, the pattern of lower unemployment with more advanced programs is evident before FOS adjustments, with the exception of graduate certificates.

The pattern of decreasing unemployment with longer programs, running from certificates to degrees, is magnified by FOS adjustments (Panel D). The unemployment rate increased by 1.8 percentage points for male certificate graduates (from 18.7% to 20.5%), decreased 1.2 percentage points for male advanced diploma and degree graduates (from 17.3% to 16.1%, and 15.6% to 14.4%), and decreased 1.6 percentage points for graduate certificate graduates (from 17.3% to 15.7%). We note that the unemployment rate for graduate certificate graduates remains higher than the unemployment rate for degree graduates after FOS adjustments.

These findings suggest that students are generally rewarded for their greater investment in longer programs, though for women this pattern is only apparent after adjusting for FOS differences across credentials. The high unemployment rate of male graduate certificates does not clearly follow this pattern, but it is difficult to interpret this finding, given that the data do not provide information about these graduates' prior education.

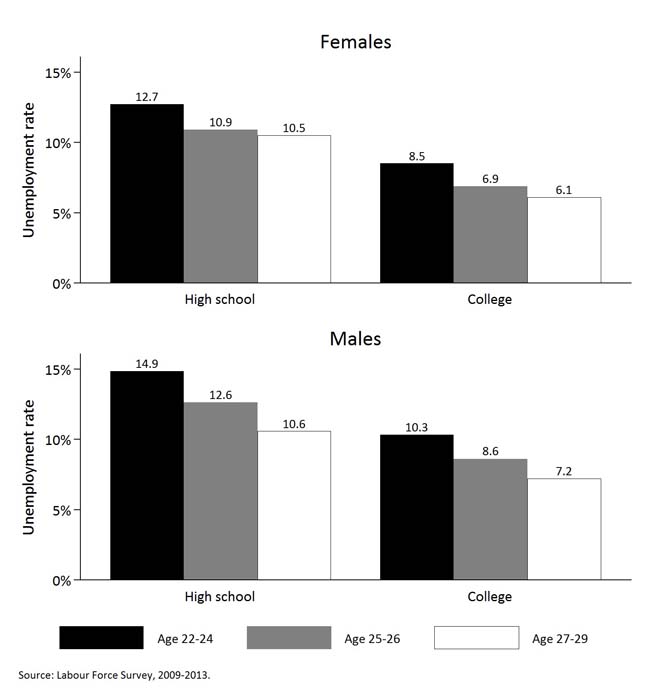

Graduates' unemployment rates decline quickly over time

A follow-up survey administered at a point in time further from graduation would be useful to examine unemployment changes as graduates have more time to gain labour-market experience. Without this data, a second best option is to use the LFS. Drawing on 2009-2013 data, we examine labour-force participants in their 20s in three age groups to see if and how much labour-market outcomes improve with age. This demographic largely represents graduates early in their careers who are gaining work experience with age.

Figure 12 presents unemployment rates of college graduates and high school graduates for three different age groups from the LFS. Comparing outcomes across age groups suggests that recent graduates' unemployment rates decline fairly quickly: female college graduates' unemployment rate declines from 8.5% at age 22-24 to 6.1% at age 27-29, while male college graduates' unemployment rate declines from 10.3% at age 22-24 to 7.2% at age 27-29. Furthermore, while unemployment rates for graduates aged 22-24 are high, unemployment rates of college graduates are consistently significantly below unemployment rates for similarly aged high school graduates.

Figure 10: Unemployment six months after graduation, GOSS, 1999-2013

Figure 11: Unemployment rates six months after graduation, GOSS, 2990-2013 (pooled)

Figure 12: Unemployment rate in Ontario by educational attainment, age group and gender, LFS, 2009-2013 (pooled)

Indicator 4: Labour force participation

Labour force participation is higher for more advanced credentials

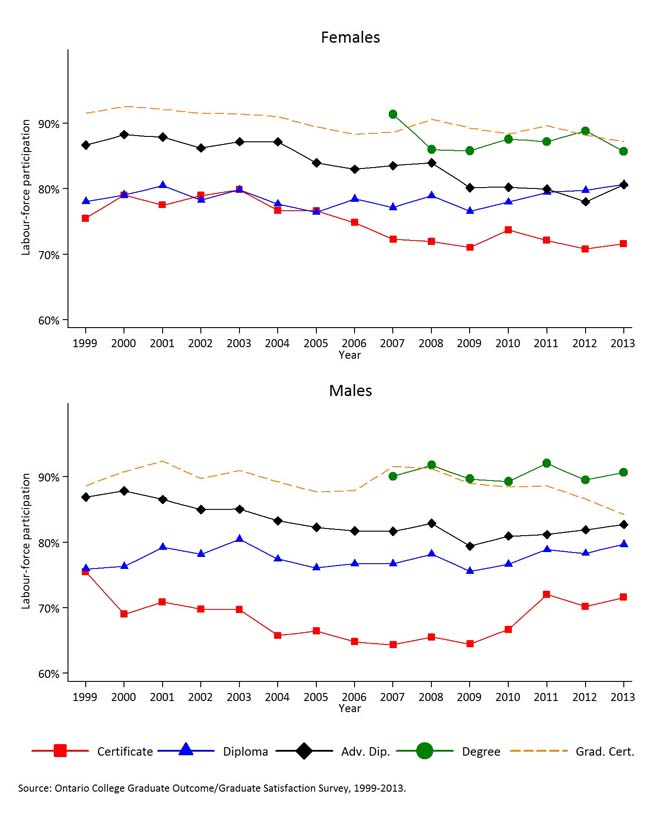

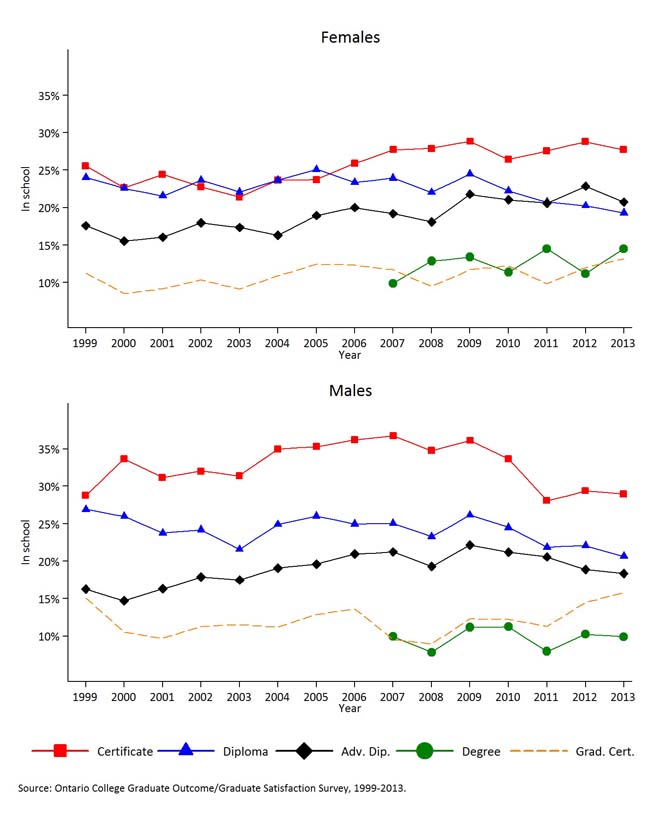

Unemployment is an important indicator on its own, but it is best understood in the context of both labour-force participation and the proportion of graduates returning to school, which is discussed in the next section. Figure 13 presents trends in the percentage of graduates in the labour force, defined as all graduates who were either employed or seeking employment six months after graduation as a percentage of the total graduate population.

The trends show that graduates of more advanced credentials are largely more likely to be in the labour force than graduates of less-advanced credentials. The exception is that female diploma graduates have labour-force participation rates similar to female certificate graduates near the beginning of the time series and similar rates to female advanced diploma graduates near the end of the time series.

The trends are fairly stable over time, though female participation declines slightly. Both male and female participation seems to be briefly affected by the 2009 recession across all credentials, though male labour force participation has mostly recovered since then. The differences between credentials are often quite large, especially the difference between certificate graduates compared to all other graduates among males.

With respect to graduates not in the labour force, from our data on the percentage of students who have returned to work, we have determined that the majority of graduates not in the labour force are pursuing further education.

Field of study adjustments magnify differences in labour force participation among certificate holders

Next we focus on the 2009-2013 period to highlight recent differences across credentials. Panel A of Figure 14 presents the percentage of female graduates in the labour force for each credential and Panel C presents the same information for male graduates. In this model, we account for differences across region and age by setting the region and age distributions for each credential to the overall distribution for all credentials in this period.

Panel B presents the percentage of female graduates in the labour force under the counterfactual condition that the FOS distribution for each credential is the overall FOS distribution for all female college graduates (the same information is presented in Panel D for male graduates). Controlling for FOS does not greatly affect the relationship between more advanced credentials and greater labour force participation; however, it does decrease the labour force participation for certificate graduates.

Figure 13: Labour-force participation six months after graduation, GOSS, 1999-2013

Figure 14: Labour-force participation six months after graduation, GOSS, 2009-2013 (pooled)

Indicator 5: Returned to school

Graduates of less advanced college programs were more likely to return to school

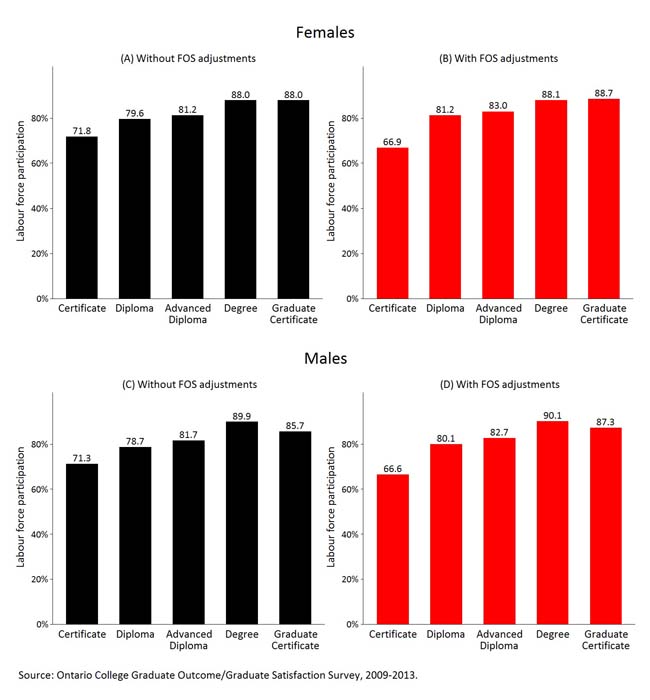

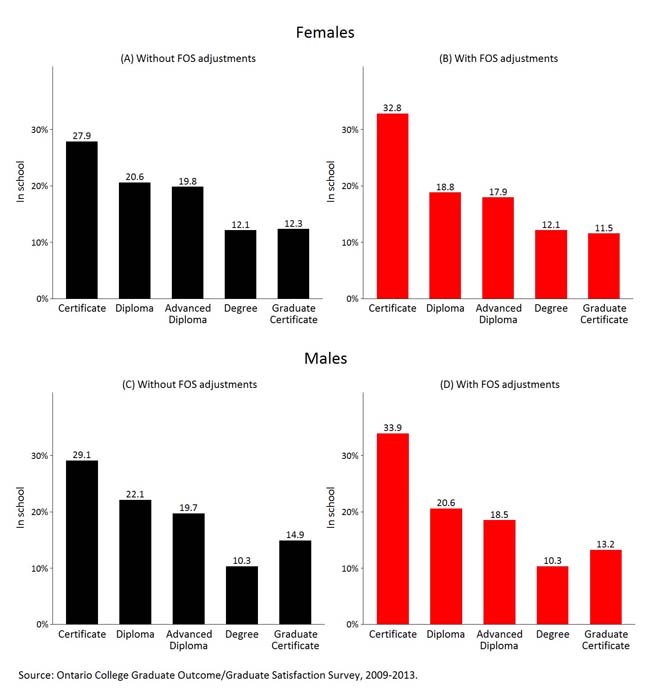

Figure 15 presents trends in the percentage of graduates attending an educational institution six months after graduation. Note that the trend lines represent the credentials the respondents obtained six months earlier, not the credentials related to the program they entered afterward.

Graduates of less-advanced college programs, especially certificate programs, were more likely to return to school. Conversely, graduates of college degree programs were much less likely to return to school than graduates of diploma and advanced diploma programs. Differences in rates of returning to school between different credentials are somewhat stable over time, and there does not appear to be any clear relationship between rates of returning to school and the business cycle. Differences across gender are largely consistent over time, although for female graduates, the percentage returning to school increased slightly over the period observed, except for diploma graduates, which remained relatively constant.

Next we focus on the 2009-2013 period to highlight recent differences across credentials. Panel A of Figure 16 presents the percentage of female graduates who have returned to school for each credential. Panel C presents the same for male graduates. In this model, we account for differences across region and age by setting the region and age distributions for each credential to the overall distribution for all credentials in this period. Controlling for age and region does not greatly alter which credential holders are most likely to return to school.

Panel B presents the percentage of female graduates who have returned to school under the counterfactual condition that the FOS distribution for each credential is the overall FOS distribution for all female college graduates (the same information is presented in Panel D for male graduates).

If the apparent decrease in the likelihood of returning to school associated with more advanced credentials were explainable by differences in the FOS in which those credentials tend to be obtained, we would see that here. The fact that controlling for FOS does not alter the picture of which graduates return to school suggests that graduates of less advanced credentials are more likely to return to school, regardless of FOS. Male graduate certificate graduates are an exception, which have higher return-to-school rates than degree graduates before and after controlling for FOS. This is surprising, given that they would have already completed at least one credential prior to their graduate certificate.

One place where controlling for FOS has an effect is on certificate graduates. For both male and female graduates it increases the relative likelihood that certificate holders will return to education.

Figure 15: Percentage of college graduates that were attending an educational institution six months after graduation, GOSS, 1999-2013

Figure 16: Regression-adjusted percentage of college graudates that were attending an educational institution six months after graduation, GOSS, 2009-2013 (pooled)

Indicator 6: Relatedness to employment

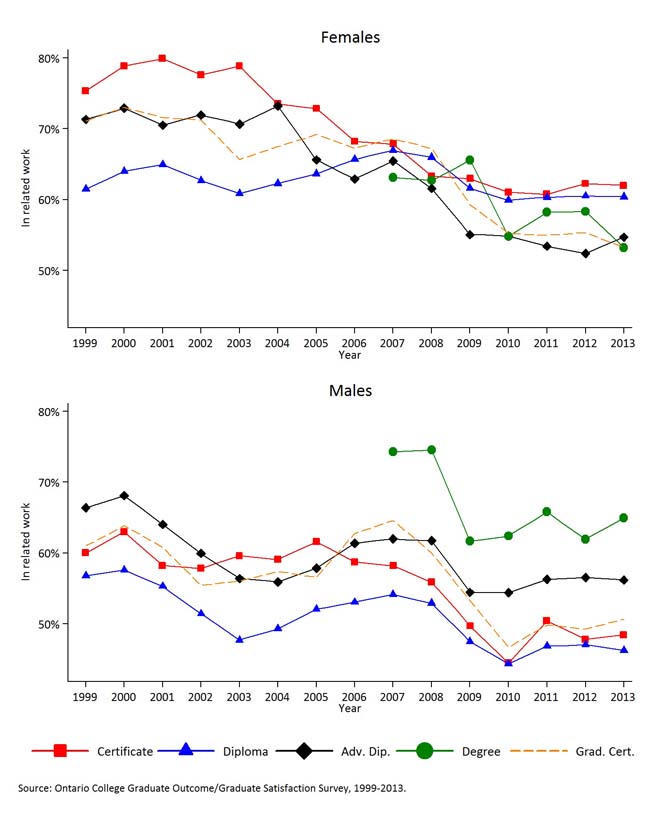

Proportion of graduates in related work declined over time across all credentials, with a more pronounced decline around the time of the recession

Figure 17 presents trends in related work among employed graduates. The lines represent the percentage of employed graduates who responded “Yes” to the question “Was this job related to the program that you graduated from?” (Those selecting “Yes, partially” are not categorized as being in related work.)

The percentage in related work declined over time for all graduates, with greater declines following the 2009 recession, and a period of stabilization thereafter.

Work relatedness varies by gender. Female graduates are more likely to be employed in related work than male graduates, with the exception of degree graduates, where male graduates are more likely than female graduates to be employed in related work.

Across credentials, there is no clear relationship between program duration and relatedness.

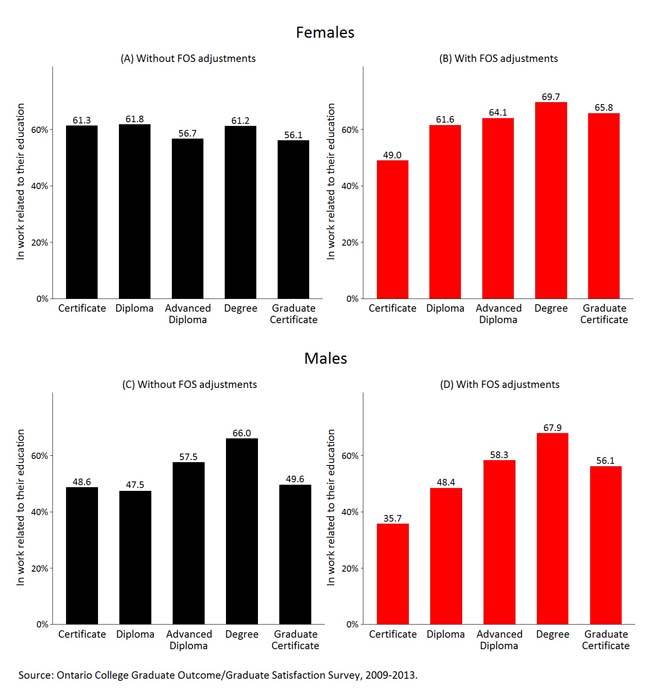

Adjusting for field of study suggests graduates of higher credentials are more likely to be employed in work related to their education

Next we focus on the 2009-2013 period to highlight recent differences across credentials. Panel A of Figure 18 presents the percentage of female graduates in related work for each credential. Panel C presents the same for male graduates. In this model, we account for differences across region and age by setting the region and age distributions for each credential to the overall distribution for all credentials in this period.

This does not greatly alter the picture of relatedness from Figure 17, suggesting that the differences between credentials are not explainable by differences in region or age of graduates.

Panel B presents the percentage of female graduates in related work under the counterfactual condition that the FOS distribution for each credential is the overall FOS distribution for all female college graduates (the same information is presented in Panel D for male graduates).

Controlling for FOS in this fashion alters the differences between the credentials for both male and female graduates. Particularly, across both genders work-relatedness increases for advanced diploma graduates, degree graduates, and graduate certificate graduates when FOS is controlled for, while it decreases for certificate graduates. This suggests that the relatively low premium to more advanced credentials in terms of obtaining related work is partially the result of the FOS being pursued. In panels B and D, graduates with more advanced credentials are more likely to obtain work in fields related to their education. Male certificate and diploma graduates are considerably less likely to be working in a related field than graduates with other credentials, or their female certificate and diploma graduate counterparts.

Figure 17: Percentage of employed college graduates employed in work related to their education six months after graduation, GOSS, 1999-2013

Figure 18: Regression-adjusted percentage of employed graduates employed in work related to their education, six months after graduation, GOSS, 2009-2013 (pooled)

Indicator 7: Satisfaction with work preparation

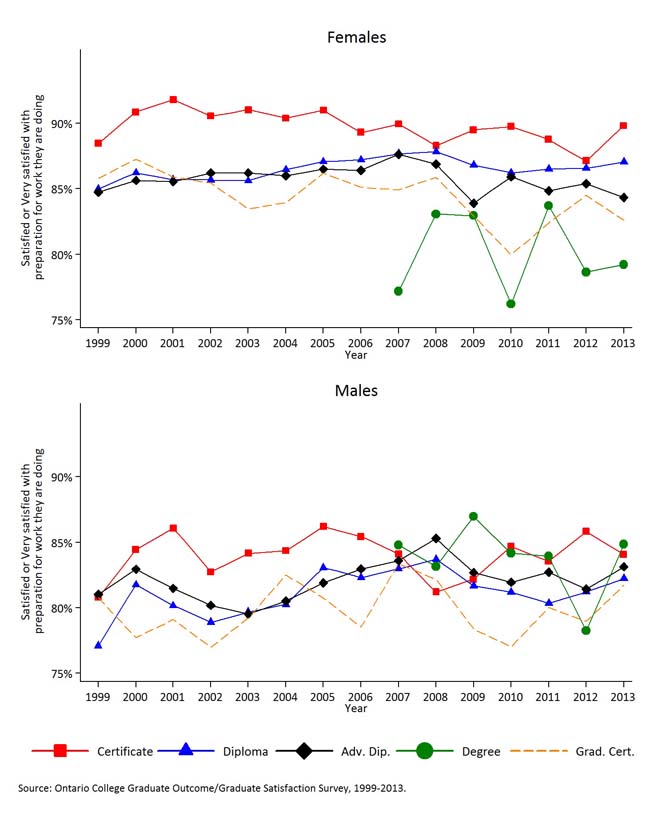

Among females, satisfaction with work preparation is generally lower for graduates of more advanced programs

Figure 19 presents trends in the percentage of employed graduates who are either “Satisfied” or “Very satisfied” with their college preparation for the type of work they are doing. The time series shows that satisfaction is generally lower among female graduates of more advanced programs, though this pattern does not seem to hold for male graduates. For male graduates, this pattern holds before the recession but not afterwards. After 2009, male graduates of certificate, advanced diploma, and degree programs tend to be more satisfied than graduates of diploma and graduate certificate programs.

Satisfaction appears to drop slightly for both genders across credentials after the recession, though the magnitude of the drop varies by credential. Diploma and advanced diploma graduates show larger overall drops than graduates of other programs, and certificate graduates show the smallest decreases in satisfaction. Graduate certificate graduates experienced a large drop in satisfaction following the recession, which has since recovered significantly.

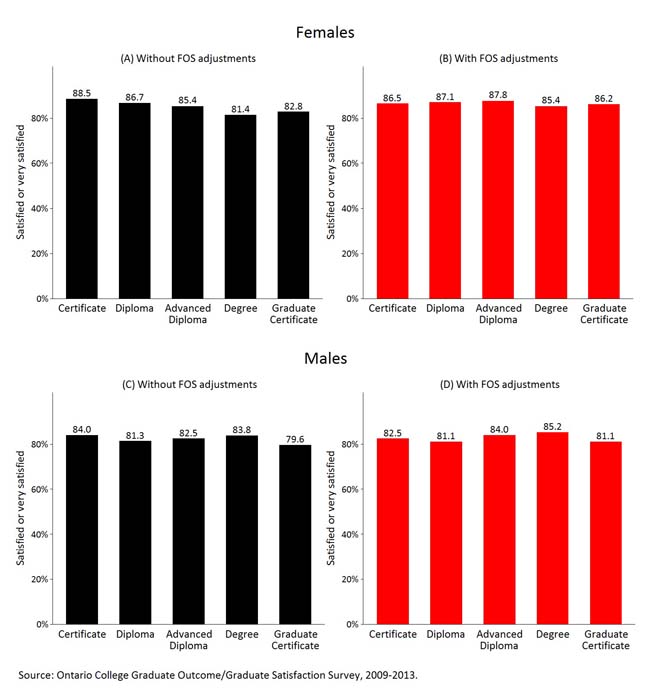

Next we focus on the 2009-2013 period to highlight recent differences across credentials. Figure 20 presents the percentage of employed graduates of each credential that are very satisfied with their college preparation. Panel A presents the percentage of female graduates of each credential who are satisfied or very satisfied (Panel C presents the same information for males). In this model, we account for differences across region and age by setting the region and age distributions for each credential to the overall distribution for all credentials in this period. In Panel B (D for males) we add the counterfactual condition that the distribution of FOS for each credential matches the overall distribution of FOS for all graduates.

Adjusting for FOS eliminates the pattern observed between credential and satisfaction among female graduates, while generally leaving the observed pattern among male graduates unchanged. When FOS is adjusted for, female graduates of more advanced credentials no longer report lower satisfaction, suggesting that the FOS pursued by female students in more advanced credentials contribute considerably to lower reported levels of satisfaction. Meanwhile, male graduates of certificate, advanced diploma and degree programs remain more satisfied than graduates of diploma and graduate certificate programs.

In spite of the decline in satisfaction observed for female graduates of more advanced credentials, females have higher satisfaction rates than males across all credentials other than degrees.

Figure 19: Percentage of college graduates satisfied or very satisfied with their work preparation, GOSS, 1999-2013

Figure 20: Regression-adjusted percentage of college graduates satisfied or very satisfied with their work preparation, six months after graduation, GOSS, 2009-2013 (pooled)

Indicator 8: Achieved post-graduation goals

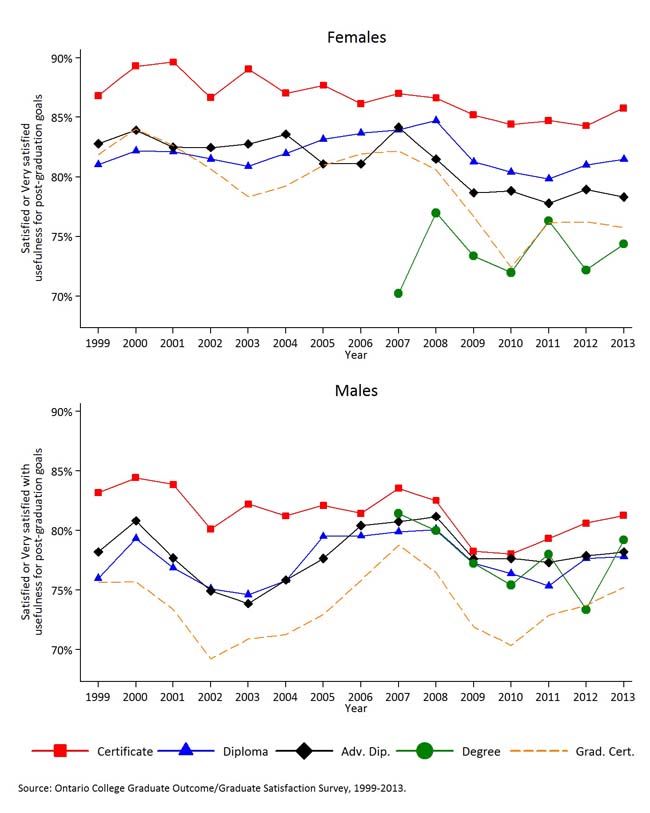

Among females, satisfaction with usefulness of program for achieving post-graduation goals is lower for graduates of more advanced programs

Figure 21 presents trends in the percentage of all graduates who are “Satisfied” or “Very satisfied” with the usefulness of their college education in achieving their post-graduation goals. This can be seen as a more inclusive satisfaction measure because it is asked of all graduates, and it acknowledges that some graduates have goals other than direct entry to the labour market, such as pursuing further education.

Overall, certificate graduates report higher satisfaction levels than graduates of other credentials. For female graduates, levels of satisfaction with usefulness of achieving post-graduate goals show a similar pattern to levels of satisfaction for work preparation, with graduates of more advanced degrees having lower levels of satisfaction. For male graduates, satisfaction is highest for certificate graduates, followed by roughly equal levels of satisfaction among diploma, advanced diploma, and degree graduates, and considerably lower levels of satisfaction for graduate certificate graduates. Graduates of most credentials expressed lower levels of satisfaction during and immediately following the 2009 recession.

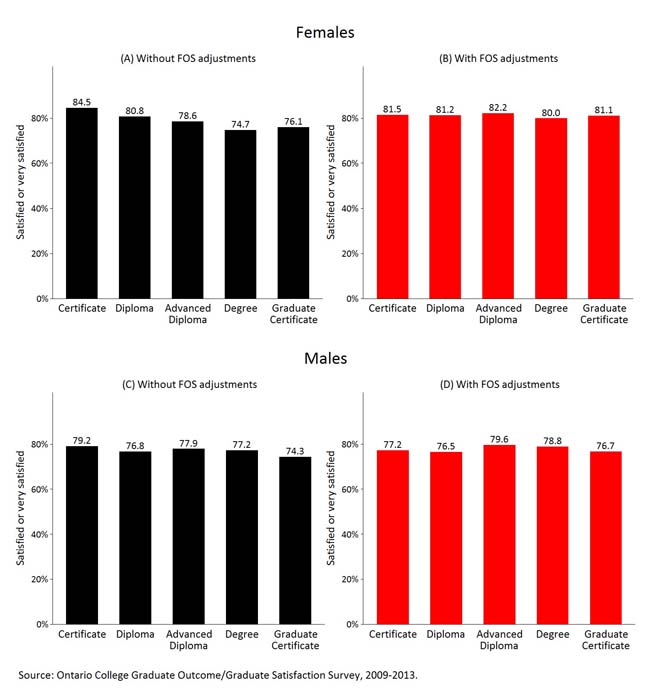

Next we focus on the 2009-2013 period to highlight recent differences across credentials. Figure 22 below presents the regression-adjusted percentages of graduates that are satisfied or very satisfied with the usefulness of their program. Panel A of Figure 22 presents the percentage of satisfied or very satisfied female graduates of each credential (Panel C presents the same information for males). In this model, we account for differences across region and age by setting the region and age distributions for each credential to the overall distribution for all credentials in this period. In Panel B (D for males) we add the counterfactual condition that the distribution of FOS for each credential matches the overall distribution of FOS for all graduates.

Adjusting for FOS roughly equalizes satisfaction levels for female graduates, increasing them for graduates of more advanced credentials and decreasing them for certificate graduates. These results suggest that lower satisfaction levels among female graduates of more advanced credentials may be associated with the fields of study being pursued in these credentials. Adjusting for FOS has little effect on satisfaction levels across credentials for males.

Figure 21: Percentage of college graduates very satisfied with ability to reach goals, GOSS, 1999-2013

Figure 22: Regression-adjusted percentage of college graduates very satisfied with ability to reach goals, GOSS, 1999-2013 (pooled)

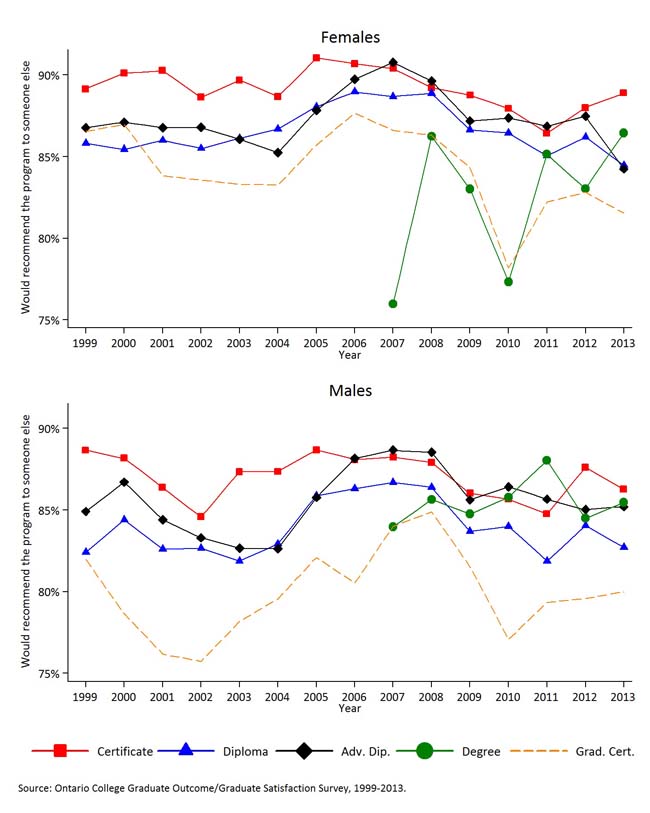

Indicator 9: Would recommend the program

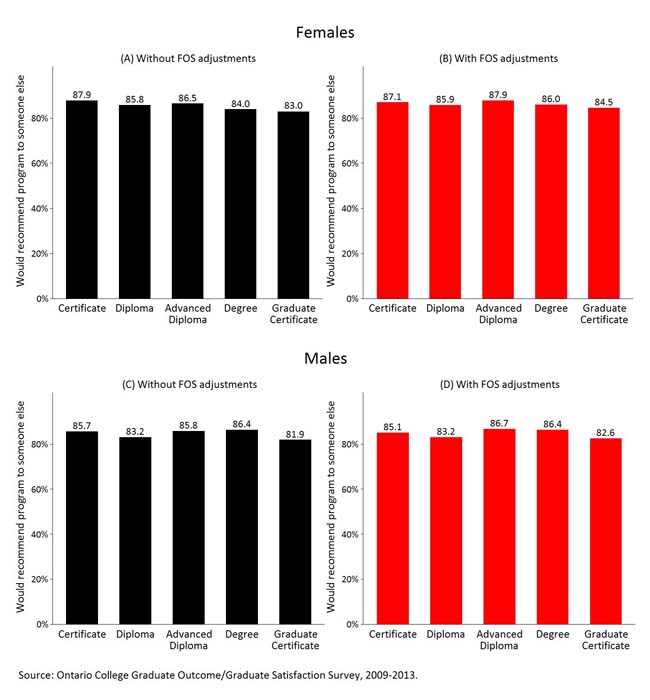

Certificate graduates and advanced diploma graduates were most likely to say they would recommend their program

Figure 23 presents trends in the percentage of graduates who state that they would recommend their program to someone else. With few exceptions, over 80% of graduates in all years and in all programs would recommend their program to someone else. For males and females, certificate graduates are the most likely to recommend their program over time, while graduate certificate graduates are generally the least likely to recommend their program. The percentage of diploma, advance diploma and degree graduates that would recommend their program falls roughly in between these two credentials.

Next we focus on the 2009-2013 period to highlight recent differences across credentials. Panel A of Figure 24 presents the percentage of female graduates who would recommend their program for each credential. In this model, we account for differences across region and age by setting the region and age distributions for each credential to the overall distribution for all credentials in this period. Panel A shows a pattern for females that is broadly consistent with the overall trends described above.

Panel B presents recommendation rates for females under the counterfactual condition that the FOS distribution for each credential is the overall FOS distribution for all female college graduates. For females, the FOS adjustment makes little difference, slightly increasing the likelihood that graduates of most credentials would recommend their program. The exception is female graduates of certificate programs, where FOS adjustments slightly decrease the likelihood of recommending their program.

Panel C presents recommendation rates for males. For men, once we account for differences across region and age and with our focus on the more recent time period, degree graduates are most likely to recommend their program. Adjusting for FOS (Panel D) slightly increases the percentage of male advanced diploma graduates that would recommend their program, putting them on par with degree graduates.

Figure 23: Percentage of college graduates that would recommend program to someone else, GOSS 1999-2013

Figure 24: Percentage of college graduates who would recommend their program to someone else, GOSS, 2009-2013 (pooled)

Summary of outcomes

|

Gender |

Certificate |

Diploma |

Advanced diploma |

Degree |

Graduate certificate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Graduation rate11 | All |

70.9% |

62.6% |

59.3% |

69.5% |

85.8% |

| 2. Annual earnings | Female |

$23,245 |

$26,257 |

$28,380 |

$28,617 |

$33,689 |

Male |

$28,858 |

$29,580 |

$34,495 |

$34,256 |

$34,686 |

|

| 3. Labour-force participation | Female |

71.6% |

80.7% |

80.6% |

85.7% |

87.2% |

Male |

71.6% |

79.7% |

82.7% |

90.7% |

84.3% |

|

| 4. Unemployment rate | Female |

14.4% |

16.2% |

15.9% |

15.3% |

15.3% |

Male |

17.0% |

18.7% |

16.4% |

15.3% |

21.5% |

|

| 5. Returned to school | Female |

27.7% |

19.3% |

20.7% |

14.5% |

13.2% |

Male |

29.0% |

20.6% |

18.3% |

9.9% |

15.8% |

|

| 6. Employed with work related to college program | Female |

62.0% |

60.4% |

54.7% |

53.2% |

53.3% |

Male |

48.4% |

46.2% |

56.2% |

65.0% |

50.7% |

|

| 7. Satisfied with college preparation for the work they are doing (% “Satisfied” or “Very satisfied”) | Female |

89.8% |

87.0% |

84.4% |

79.2% |

82.6% |

Male |

84.1% |

82.2% |

83.2% |

84.8% |

81.7% |

|

| 8. Satisfied with usefulness of college education for reaching post-graduation goals (% “Satisfied” or “Very satisfied”) | Female |

85.8% |

81.5% |

78.3% |

74.4% |

75.8% |

Male |

81.3% |

77.8% |

78.2% |

79.2% |

75.2% |

|

| 9. Would recommend program to someone else | Female |

88.9% |

84.5% |

84.2% |

86.4% |

81.5% |

Male |

86.3% |

82.7% |

85.2% |

85.5% |

80.0% |

8 Graduation Rates are collected by the college at the end of the completion timeframe for all colleges. They are then reported to the Ministry one-year later (reporting year).

9 As of January 1, 2005 all new applicants for professional registration with the College of Nurses of Ontario must complete a bachelor's degree in Nursing.

10 While the trend data being examined generally cover the years 1999-2013, regression analysis is only performed on data from 2009 to 2013. The primary reason for this is that College degree program enrollment was too low before 2009 to be accurately modeled: as a result, data only from 2009 onwards can be used for degree program outcomes to be comparable to outcomes from other credentials. Note that the 2009 recession produced a major discontinuity in labour market trends. While starting the regression analysis in 2009 eliminates this discontinuity, it is important to be aware that labour market outcomes are likely to be naturally improving over this period as economic conditions are improving more broadly.

11 Graduation rate is measured in 2012. All other indicators are from the 2013 GOSS, measured 6 months after graduation.