Chapter 4 – Findings from other jurisdictions

Introduction

A key component of this review was to recent trends and proposals in Ontario within the context of broader trends in postsecondary education and an exploration of how other jurisdictions have responded. As part of this work, we examined the credential mix in seven jurisdictions: Alberta, British Columbia, Oregon, Washington, Wisconsin, England and Ireland. This chapter presents the results of these analyses. Section I identifies key trends in postsecondary education; Section II looks at these trends through a detailed exploration of the seven jurisdictions.

Section I – Situating Ontario within the context of global trends

Below, we explore the evolution of Ontario's postsecondary education system within three key trends:

- Evolution of systems, institutional mandates and differentiation

- A focus on innovation to facilitate student labour market transitions

- An increased emphasis on quality alignment, outcomes, and transparency

Trend 1: Evolution of systems, institutional mandates and differentiation

Like Ontario, jurisdictions around the world have responded to increased participation in tertiary education through the evolution of their systems. This has included the addition of institutions, the expansion of existing institutions' mandates, and a focus on system design to support access and quality learning outcomes.Ontario

In Ontario, the increase in demand for postsecondary education places after WWII was met by expanding enrolments in established universities and by creating new institutions. There were 14 universities in the early 1960s; today there are 20. Alongside the enrolment challenge in the post-war period was a perceived need to accommodate emerging labour market demands for skilled workers. The response was the creation of Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology. Legislation was introduced in May 1965 and the first colleges opened in 1966. There were 20 CAATs by 1970; today, there are 24.

Perhaps the most notable evolution was the introduction of the Postsecondary Education Choice and Excellence Act, 2000 that authorized colleges to seek ministerial consent to offer degrees in applied areas of study. Ontario colleges received a new orientation with the passage of the Ontario Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology Act, 2002. The Act increased the autonomy of the colleges and relieved them of geographically defined catchment areas. These changes also led to increased differentiation in the college sector by establishing a new class of institutions, the Institutes of Technology and Advanced Learning (ITALs) (HEQCO, 2009). In 2002, the Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities received business plans to differentiate colleges as ITALs, with a threshold of up to 15% of programming in degrees of applied areas of study, while CAATs could offer degrees in applied areas of study with an overall cap of 5% within their programming. In 2003, ITAL and “ITAL-like” colleges were approved: Conestoga, George Brown, Humber, Seneca and Sheridan. Georgian was also captured in this differentiation model, but focused on the establishment of a separate unit in the college, emphasizing university partnerships. The differentiated colleges signed accountability agreements with the province in 2004, after which a moratorium was placed on college differentiation.

Europe

In the 1960s and 1970s a variety of polytechnic systems were founded across Europe to deliver short-cycle vocational and technical education (Slantcheva-Durst, 2010). Over time, these polytechnics expanded their output into university level degrees, and a new system of career-oriented colleges emerged to fill the short-cycle role that they had vacated (Slantcheva-Durst, 2010). For this reason, the relationship between colleges and universities in Europe is often described as a parallel one, in that in many jurisdictions applied credentials are delivered by the colleges up to the doctoral level. The high demand for vocationally oriented baccalaureate education is in part a consequence of the high proportion (56.2%) of secondary students in Europe who are enrolled in vocational programs (OECD, 2007). The role played by former polytechnics in Europe in the provision of undergraduate education is considerable. For example in Germany, about one third of undergraduates study at the fachhochschulen; in the Netherlands, two-thirds of undergraduates study at the hogescholen; and in Ireland about 40% of undergraduates study at the Institutes of Technology (Skolnik, 2012).

United States

In the United States, community colleges have long been involved in the provision of education leading to a baccalaureate by providing the first two years of undergraduate arts and science education through Associates of Arts and Science degrees. (Russell, 2010). More recently, American community colleges are delivering senior (the last two years) of undergraduate education as well. Florida was the first state to authorize community colleges to grant applied baccalaureate degrees in 2001. By 2012, 22 states had expanded the mandate of their community colleges in a similar way (Michigan Community College Association, 2012). As of 2010, there were 465 four-year degree programs (up from 128 in 2004) being offered at 54 US community colleges, with nursing and teacher education being the most popular fields of study (Russell, 2010). There are different institutional models associated with the community college baccalaureate: in some states only one or two colleges have been authorized to begin granting degrees, and those institutions have subsequently evolved into four-year institutions, no longer offering traditional community college programs (e.g., Arkansas, Louisiana, and Utah). In other states, the colleges have maintained their traditional functions, while beginning to offer a few baccalaureate programs (Russell, 2010).

New Zealand

HESA (2012) discusses the experience in New Zealand of allowing colleges to begin awarding degrees as being particularly relevant to Ontario due to the fact that the relationship between their universities and colleges has historically been similar to ours. New Zealand's colleges traditionally offered sub-baccalaureate applied education and had close ties to local industry. In 1989, the New Zealand government passed legislation allowing colleges to grant degrees (including postgraduate degrees), provided they had the staffing, resources and research capability to do so, under the rationale that outside of these criteria the nature of the institution providing the education should not determine the level of credential awarded (HESA, 2012). In recent years, there has been a trend towards scaling back the degree granting role of colleges, in a move towards emphasizing the distinct roles of the different sectors within the system. Between 2002 and 2009 the percentage of college students in degree programs fell from 17 to 12 percent (HESA, 2012). According to HESA, however, this decline has not raised the issue of ending degree provision at colleges.

Box 5 : The case for differentiation

Many countries now have differentiated postsecondary systems comprised of universities that are research intensive, universities focused on undergraduate instruction, as well as a variety of institutions delivering workforce related instruction (Altbach et al., 2009). Grubb (2003) notes that some countries have chosen to meet the increased demand for postsecondary education by expanding their universities while others have elected to create or expand the mandate of institutions in the non-university sector. These institutions, which he refers to as “tertiary colleges and institutes” have grown in number and scope because they are perceived to have “greater flexibility, greater access and equity, more overtly occupational and economic goals, [and] a different approach to research and public service” (p. 2). Some jurisdictions maintain quite distinct separations between the sectors while others focus on relationships and mobility of students across the institutional spectrum.

Differentiation promotes institutional quality and system competitiveness by enabling each postsecondary institution to grow preferentially in those areas where it already excels, or aspires to excel. Higher quality programs mean that the credentials students receive upon graduation are more highly valued; this makes the students more competitive relative to those from other jurisdictions and makes institutions more attractive to international students. Greater differentiation offers students clearer choices from a larger number of higher quality programs, clarifies the institutions that best serve their career and personal aspirations, and facilitates mobility and transitions between institutions. Differentiation promotes accountability because it clarifies the expectations of each postsecondary institution and allows for a clear assessment of whether the postsecondary institution is meeting expectations of its differentiated mandate. (Weingarten & Deller, 2010).

Differentiation is also seen as a more fiscally sustainable approach to higher education funding. As discussed above, the significant expansion of postsecondary enrolment, programs and services has led to an increase in cost to the public. As a result, governments have begun to look at whether their public institutions can be better coordinated in order to ensure both effective and efficient delivery of postsecondary education. Strategies include the establishment of sectors that have different mandates but are aligned to ensure that students can move seamlessly though the system. Often, specific mandates are assigned to sectors or institutions, particularly concerning the nature of programs, credentials awarded and research activities.

Trend 2: A focus on innovation to facilitate student labour market transitions

Jurisdictions are taking steps to ensure that students have the right educational opportunities to support successful labour market transitions. Jurisdictions are increasing students' options to participate in various types of work-integrated learning. We also observed more bottom-up examples of very ambitious partnerships, where employers or industry consortia collaborated with institutions to create new programs, jointly investing in students over several years to fill future skill needs.No “one-size fits all” approach to applied education

Occupational skill requirements are changing. Many of today's jobs are increasingly technical in nature. But increasing technicality is only one part of the story. Employers hiring in occupations that traditionally required a vocational credential are seeking candidates who are also critical thinkers and strong communicators.

The Ontario postsecondary system is responding to students' choices with more applied learning options. As our analysis of student outcomes indicates, college certificate, diploma, and degree programs in applied areas are meeting the changing needs of students and employers. Universities too have moved to increase their offerings of labour market relevant degree programs and to improve connections between school and work. Both sectors are innovating through collaborative credential options that blend applied and academic learning, which are increasingly popular among students.

Introduction of new and modified credentials

We can see evidence of the demand for combination of applied and academic learning through the types of new credentials recently implemented elsewhere. A blend of advanced technical and transferable skill development is at the core of many of the credentials recently introduced in other jurisdictions. As we discuss in more detail below, six of the seven jurisdictions we studied have created new credentials in applied areas of study (e.g., applied Master's and Bachelor's degrees, graduate certificates, two-year applied degrees, and career pathways certificates).

Recognizing the needs of many students to move in and out of education and employment cycles, many jurisdictions are focusing on the provision of laddered or stackable credentials that create greater flexibility for students. Universities are increasingly offering applied and short-cycle (sub-baccalaureate) credentials (Tremblay et al., 2012) at the same time that traditional providers of short-cycle and applied credentials have been moving into the realm of degree level provision (often in applied fields of study) in many jurisdictions (HESA, 2012).

Modularized occupational credentials that integrate bridge training

Emerging evidence suggests that programs may improve student outcomes by offering basic skills training in the context of specific workplaces or specific post-secondary technical programs, offering accelerated learning pathways, and providing learners with wraparound services (Foster, Strawn & Duke-Benfield, 2011). For example, several studies showed that the Center for Employment Training's blend of occupational and basic skills education led to increased employment and earnings for participants, even those who entered without a high school diploma (Pearson et al., 2010; Wiseley, 2009).

Similarly, a study of Community College of Denver's FastStart program found that students performed better than the college's general remedial education students. FastStart condensed two levels of pre-college education into one semester by using contextualized instruction and wraparound support services. This model was replicated for out-of-school youth through the Colorado SUN project, which showed similar results (Bragg, 2010).

Jurisdictions are also recognizing the need for participants to earn an income while increasing their skills. Accelerated training and flexible, modular designs allow learners to balance work and learning more effectively than with traditional education and training programs.

Alongside this evolution in the skills being delivered in applied education, universities and other degree granting institutions are developing innovative ways to help their students transition into the world of work. These include expanding work-integrated learning opportunities, collaborating with colleges to deliver a blend of applied and academic learning, and building stronger connections with employers in curriculum design and for career exploration and development.

Work-integrated learning

The labour market is increasingly dynamic and the skills needs of employers are rising. For these reasons, there is an increasing concern with building students connections to the labour market, through increased information and opportunities for career exploration. Other jurisdictions are working to provide more WIL opportunities for students. The United Kingdom and Australia recently conducted major reviews of work-integrated learning. The UK review and preliminary findings from Australian research suggests WIL is associated with improved student labour market transitions, including graduate work readiness, and employment and earnings outcomes immediately after graduation (AWPA, 2014; Wilson, 2012).

Co-op programs are an important part of Ontario postsecondary education, particularly the University of Waterloo. Waterloo has more than 18,000 co-op students, more than double the number of students in any other program in any country (University of Waterloo, n.d.). In a recent HEQCO survey, one in five Ontario college graduates and one in ten Ontario university graduates had participated in co-op education (Sattler & Peters, 2013). In terms of work-integrated learning more broadly, of the students HEQCO surveyed, more than two-thirds of college students and about two out of five university students were graduates of programs with some kind of WIL component (Sattler & Peters, 2013). However, this research also suggests that WIL is underused by university students, largely because universities have not institutionalized WIL the way colleges have. Not enough employers, especially smaller firms and organizations, take sufficient advantage of WIL.

As discussed in Chapter 3, student groups we consulted expressed a desire for more WIL opportunities in universities, including at the graduate level. According to our analysis of the 2011-2013 College Graduate Survey data, about half of college students participate in some form of work-integrated learning. College students who participated in work-integrated learning have higher earnings relative to students who do not undertake some form of work-integrated learning. They were also more likely to be employed in work related to their program.

For university students, we were only able to isolate students who participated in co-op, and so have no analysis of other types of WIL. According to our analysis of the Ontario University Graduate Survey, co-op graduates had higher earnings, lower unemployment rates (at six months and two years) and were more likely to be employed in related work, relative to non-co-op students. These results are consistent with what Walters and Zarifa (2008) found for both college and university graduates, using the NGS survey of Canadian graduates in the year 2000.

Recent HEQCO research surveying graduates from 13 Ontario postsecondary institutions found similar benefits for university students and found for college students that they were more likely to be employed in work related to their program. Unlike our analysis, however, they did not find an earnings premium for college WIL participants (Peters et al., 2014).

This research was part of a series of recent HEQCO-funded studies on work-integrated learning, including interviews with expert informants, surveys of faculty, graduates, employers and a follow-up of graduates (Sattler, 2011; Peters, 2012; Sattler & Peters, 2013; Sattler & Peters, 2012). The authors made a number of recommendations, which are significant for better using work integrated learning to accelerate student transitions to the labour market:

- Increased opportunities for employer feedback and employer-institution communication in general (Sattler, 2011; Sattler & Peters, 2012).

- Longer programs (Sattler & Peters, 2012).

- Clearer, more standardized terminology (Sattler & Peters, 2012; Sattler & Peters, 2013).

The current effectiveness of WIL suggests that expanding it will improve both college and university graduates' outcomes. We note that substantial ‘disruptive' innovation is already happening in Ontario. A key example is “zone learning” at Ryerson University. In the zone or incubators, students experience a collaborative community where they work to solve industry problems or create new products. With on-site advice from faculty, industry experts and entrepreneurs, students have the space to create start-ups or work with business. “Rather than students having to find a job, they are job creators” (CCC, 2014).

Deep employer partnerships that bridge school and work

In addition to traditional forms of WIL, within Ontario and in other jurisdictions we observed the emergence of deep partnerships between employers and institutions, often involving multi-year WIL experiences and curricula designed collaboratively with consortia of regional employers. Examples of promising models that already exist in Ontario include:

- Siemens Engineering and Technology Academy (SCETA) – a partnership with five Canadian postsecondary institutions that offers PSE students a series of paid work-placements with Siemens over the course of their program, and Siemens providing tuition and professional development support. SCETA students work for Siemens for four years following graduation (Siemens, 2014).

- IBM's Employment Pathways for Interns and Co-ops (EPIC) – offers students co-ops and internships designed to build students' skills, familiarize them with IBM's organization and work style, and allow them to “take IBM for a test drive” (IBM, n.d.).

- The Cisco Networking Academy Program — Through partnerships with institutions and other organizations, students complete hands-on learning activities and network simulations to develop practical skills that will help them fill a growing need for networking professionals around the world. Students prepare for entry-level ICT jobs, additional training or education, and globally recognized certifications (Cisco, n.d.).

Conceptually, these types of partnerships appear to address a range of issues related to student transitions to the labour market. Students receive an education that meets today's employer needs, access substantial work-integrated learning opportunities, and are often hired immediately upon graduation. Institutions benefit from delivering a high-value, in-demand product. Meanwhile, employers take ownership over the ‘skills gap' by helping shape the postsecondary sector and by investing in workforce development.

Credit transfer and collaborative programming

Ontario, like other jurisdictions, is experimenting with ways to connect school and work to foster a culture of lifelong learning. This involves building clear articulation paths between credentials and strong relationships between institutions in order to make learning portable, stackable, flexible, and accessible. Core to these strategies is a desire to better value prior learning and build stronger connections with skill development that takes place in different places, at different times, inside and outside of the classroom.

- In North America, there is an increasing focus on credit transfer and stronger articulation between sub-bachelor credentials (often applied in nature), and degree-level credentials. We also observed a proliferation of short post-graduate credentials students can take to supplement their diploma or degree.

- European jurisdictions are developing qualification frameworks that use learning outcomes to clearly state how one credential articulates into the next, and are building a common credit transfer and accumulation system to allow students to carry their learning with them wherever they go.

During our scan of the current state in Ontario, we observed significant innovation and growth in collaborative programs. These programs allow students to combine applied and academic learning in various ways—and in some cases accelerate a student's pathway to the labour market. Notable examples include:

- Preparatory certificates that qualify students to enter degree programs (system-wide Pre-Health program.)

- Integrated collaborative degree/diploma programs (Guelph-Humber, UTM-Centennial and Sheridan)

- Fully integrated collaborative degree programs (York and Sheridan's Bachelor of Design)

- 3+1 integrated collaborative degree-graduate certificate programs (Brock and multiple college partners)

Demonstrating skill development to students, employers and institutions

Graduates may have difficulty articulating their knowledge and skills to employers. Ontario research on the issue is scarce but consistent with the views expressed during consultations (Martini & Clare, 2014). If students cannot articulate their skills and if they are unable to understand how skills are acquired through their learning experiences, they may have difficulty leveraging them when they enter the job market.

Documenting learning can help students understand the skills they develop in their education. Studies have shown that students can perform tasks without being able to articulate the task itself or why they are doing it (Reber & Kotovsky, 1997; Sun, Merrill & Peterson, 2001), and that making students explicitly aware of the skills they develop can improve student learning and the ability to articulate their learning (Hagerty & Rockaway, 2012).

There has been a wealth of innovation by institutions, foundations and governments seeking to assess and recognize student achievements in a way that is valuable to both students and employers. Our research found that other jurisdictions are developing approaches to improve the documentation of student learning. In Europe, Diploma Supplements are granted to all students, and function as a comprehensive transcript that includes statements of the knowledge and skills students acquire from successfully completing a program.

Our research identified three prominent approaches other jurisdictions are experimenting with to help students demonstrate and articulate their workplace skills:

- Badges are an innovative way for learners to signal the mastery of specific skills or competencies. Although in their early stages, badges may serve as a useful concept to document and assess a much wider range of student development than traditional academic transcripts, which are mostly content-based. In 2011, Mozilla, HASTAC and the MacArthur Foundation led a collaboration to produce standards to allow any organization to create, issue, manage and verify digital badges. This process culminated in 2013 with the development of Open Badges Infrastructure (OBI) software, a free online tool.

- e-Portfolios are electronic collections of artifacts (written work, presentations, electronic badges, academic awards) which demonstrate a student's learning. They are being used across a broader range of disciplines than is traditionally the case with hard-copy portfolios. E-Portfolios are used throughout the learning process as a space where students can document their learning goals and measure progress towards these goals. Students collect evidence and examples throughout their learning of how they have mastered the skills and knowledge they sought (University of Waterloo Centre for Teaching Excellence, n.d.). As such, they bring continuity to a learning environment defined by combinations of individual courses. Through the act of reflecting on learning goals and outcomes, e-portfolios are seen as an important part of making learning outcomes explicit and meaningful to students and instructors.

- Credential supplements, tools to help students articulate their learning achievements, are common in Europe and are growing in popularity in North America. In Europe, Diploma Supplements are awarded to students automatically upon graduation in most countries. The Diploma Supplement is one of five documents of the Europass,1 a template that students can use to communicate their qualifications (European Commission, 2012). Similarly, institutions in the U.S. are experimenting with competency-based transcripts (Fain, 2013a). Badges and e-portfolios may also serve as credential supplements.

Considerable experimentation is ongoing in Ontario; for example, Brock University, York University, Ryerson University, St. Lawrence College and George Brown College among others have recently implemented software for documenting co-curricular activities (Martini & Clare, 2014). We found examples of such experimentation in every jurisdiction we surveyed.

One of the most prominent Ontario examples is Magnet. Magnet is a career-networking platform developed by Ryerson University that collects data on individual students' skills and employers' needs to improve the match between recent graduates and prospective employers. The Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities recently announced $1.2 million in funding to expand the Magnet program, which is already in operation at 18 Ontario colleges and universities (Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities, 2014).

Competency-based education and assessment

Competency-based education (CBE) is a style of program delivery where students receive recognition for being able to demonstrate competency, and receive credentials for accumulating sets of competencies (Klein-Collins, 2013).

The most long-standing example of an institution awarding CBE credentials is Western Governors University — a non-profit, online, accredited university, founded in 1997 by 19 U.S. governors (WGU, n.d.). Rather than complete a series of courses to obtain a credential, students at WGU are required to show mastery over a number of domains. Each domain is composed of a series of competencies, and the competencies in turn are subdivided into sets of objectives that form the building blocks of assessment (Staker, 2012). The WGU model has been replicated many times in the United States; we saw an example of a similar new program in our jurisdictional scan in the Wisconsin Flex Option.

Competency-based education has the potential to create value in a number of ways:

- CBE is a natural delivery model for outcomes based education. Since students receive recognition for being able to demonstrate abilities, the skills they develop are clear — giving students, parents, institutions, governments and employers a clearer picture of the impact of PSE (Weise & Christensen, 2014).

- CBE has the potential to increase the productivity of educational delivery, while improving students' learning. By putting content delivery online, and targeting faculty time to where it is most needed, students can potentially receive more individual attention without increasing the workload of the professoriate.

- CBE facilitates prior learning assessment and recognition (PLAR) because students are recognized for the skills they have, not for how or where they acquired them.

- CBE facilitates just-in-time and life-long learning because it proceeds at the student's own pace, and is not dependent on a set number of hours spent in lectures.

Trend 3: An increased emphasis on quality alignment, outcomes, and transparency

Ontario's policy priorities are increasingly quality-focused. The primary goal of its differentiation policy framework is to promote educational quality while maintaining system sustainability. Ontario's Qualifications Framework is a comprehensive information tool that aligns with pan-Canadian degree standards and includes statements of learning outcomes for sub-bachelor degree credentials. To our knowledge, the Ontario college system is one of the few postsecondary sectors in North America with program level learning outcomes. With HEQCO's support, Ontario postsecondary institutions have also been actively engaged in global research efforts to advance learning outcomes articulation and assessment.

However, Ontario is also singular in its approach to quality assurance with the existence of three quality assurance bodies, with no formal mechanism to align interpretation of the OQF for quality assurance standards, policies, and processes for individual sectors and institutions. We look at this issue in more detail in Section II. Below, we map the global trend towards greater alignment of quality assurance standards and processes, and the role of learning outcomes assessment in facilitating this process.

Alignment of quality assurance standards and processes

The Bologna Process and its related reforms are a commitment on behalf of 47 countries to create a common higher education space in Europe. For the past fifteen years, signatories to the Bologna Declaration have worked to improve the comparability and compatibility of their higher education systems, as well as the mobility of their students and graduates. Their example has inspired initiatives in inter-jurisdictional alignment by U.S. states, countries in Latin America, the African Union, and 27 countries in the Asia-pacific region (Altbach et al., 2009; Lumina Foundation, 2014). Prior to the Bologna process, European jurisdictions varied widely in their structure and approaches to quality assurance for postsecondary education. The amount of time that a student could be expected to spend completing a first degree ranged from three years (in Britain) to six years (in Germany and parts of Scandinavia where the first degree was a master's). For this reason, students had difficulty achieving recognition abroad both from other educational institutions and from prospective employers. Because labour mobility is a founding principle of the European Union, these difficulties have prompted European countries to confront the issue of student mobility and credential recognition across borders (Usher & Green, 2009).

The European Qualifications Framework for Lifelong Learning defines learning outcome standards as principles, and explicitly references applied and academic education in the description of expected knowledge, skills and competencies of baccalaureate degree graduates (EQF-LLL, 2008).

It should be noted that in contrast to Europe, North American jurisdictions have historically had highly consistent degree structures. Regional accreditation agencies in the U.S. ensure that postsecondary institutions meet minimum quality standards across vast regions of the United States. As a result the driving impetus for “Bologna-like” reforms is considerably less apparent in North America. However, while we did not find evidence that North American jurisdictions could benefit from a “Bologna-like” alignment, some of the tools developed as part of the process may be relevant.

In Canada, the Ministerial Statement on Quality Assurance of Degree Education in Canada (CMEC, 2007) commits provinces to meet minimum learning and quality assurance standards for degree-level credentials. Like Ontario, BC and Alberta align their degree-level outcomes with the CMEC degree-level standards. These jurisdictions also make distinctions for degrees in an applied context. For example, BC and Alberta express minimum faculty requirements in principles, and in Alberta's case, faculty requirements emphasize professional work experience for applied degree programs (CAQC, 2011; DQAB, 2008).

Learning outcomes assessment

The quality of higher education has traditionally been measured by the inputs (e.g., library holdings) and outputs (e.g., publications) of higher education institutions. These measures, while useful, are increasingly seen as flawed and incomplete indicators of the quality of education provided (Hazelkorn, 2008; Rauhvargers, 2011). In turn, there is a growing interest in learning outcomes as the basis for student and quality assessment. Learning outcomes are statements of what a student is expected to know and do after a process or period of learning (European Commission Education and Culture, 2008).

A focus on learning outcomes has the potential to transform education quality assurance and accountability in a number of ways:

- Student-focus: learning outcomes shift the emphasis of quality assessment away from inputs and outputs and towards whether students actually learn what they're intended to.

- Transparency: by providing objective statements of the expected outcomes of education, learning outcomes serve as a transparent tool for students, employers, and governments to understand the quality of education provided by higher education institutions.

- Performance improvement: assessment based on learning outcomes provides objective feedback on institutional performance. Learning outcomes have the potential to serve as a superior tool for program and curriculum development and improvement, as well as for the enhancement of teaching practices more broadly.

- International comparability: learning outcomes transcend national borders, cultures and languages, allowing for a greater international and comparative understanding of the quality of institutions and programs. (Lennon, 2014; Tremblay, 2012)

There have recently been several major attempts to define and measure student learning outcomes: Tuning, which is part of the Bologna Process, the OECD's Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO) project, the Council for Aid to Education's Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA) tool, and the Australia Graduate Skills Assessment. We summarize each of these below:

- Tuning: Tuning is the process of identifying learning outcomes associated with particular disciplines at particular credential levels. It originated during the European Bologna framework as a way of ensuring that credential outcomes within disciplines were comparable across jurisdictions. Through consultations with graduates, employers and academics, the Tuning model identifies key learning competencies (in terms of skill, knowledge, and content) for individual subject areas (Wagenaar, 2008). These general competencies become reference points to which higher education institutions can “tune” their own programs to improve comparability, while preserving regional autonomy and diversity.

- Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA): The CLA was developed in 2002 by the Council for Aid to Education (CAE), a U.S. non-profit organization whose purpose is to improve quality assessment in higher education. The CLA seeks to measure the value added by an educational experience by testing students on specific learning outcomes at the beginning and end of their programs. The CLA was designed to measure a student's critical thinking, analytical reasoning, problem solving, and written communications skills. These “broad abilities” were selected because they are common objectives of most academic programs and are often a stated objective of higher education institutions (Klein et al., 2007).

- Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO): AHELO is a feasibility study undertaken by the OECD to determine the practicality of defining and assessing disciplinary learning outcomes across jurisdictions (Tremblay et al., 2012). Experts and practitioners from 17 countries (including Ontario - 10 universities) came together to define and assess learning outcomes in two disciplines (economics and engineering), while also attempting to account for unique contextual characteristics of jurisdictions, and to estimate the value added by a learning experience. AHELO used the TUNING methodology to identify learning outcomes, and the CLA methodology to test value added learning.

- Australia Graduate Skills Assessment: The Australia Graduate Skills Assessment has been used since 2004 to assess the skills of students at the beginning and end of their programs. The four competencies included in the test are: critical thinking; problem-solving; interpersonal understandings; and written communication. The assessment is designed to provide information about certain key generic skills in students (Australia Council for Educational Research, 2014).

In 2011, HEQCO initiated a comprehensive research plan focused on learning outcomes, which resulted in three pilot initiatives that are at the forefront of global experimentation in defining and/or measuring learning outcomes — the Collegiate Learning Assessment, the OECD's Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes, and Tuning.

A key learning from these experiments is that Ontario postsecondary institutions can successfully collaborate to define the learning outcomes associated with a period of learning; however, there is substantial room for more work in how Ontario measures whether students actually meet these learning outcomes (Lennon et al., 2014). Ontario participation in the Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes project and the demonstration of the Collegiate Learning Assessment was successful in providing proof of concept (i.e., that it is administratively possible to implement a standard assessment online, in a common way, to students around the world), but also demonstrated the complexities of implementation and administration.

To this end, HECQO recommended that future experiments to measure learning outcomes include appropriate incentives for student participation in order to generate more reliable and representative results (Lennon, 2014; Lennon & Jonker, 2014). In a similar vein, HEQCO's most recent research plan suggests that the most feasible way of measuring learning impact is by incorporating measurements of learning outcomes into regular student assessment, and thereby making them relatively less onerous for students (HEQCO, 2013).

Our analysis of global trends and select jurisdictions indicates that substantial progress is being made around the world in defining learning outcomes associated with postsecondary education. Here, like elsewhere, the next frontier in learning outcomes is figuring out how to measure them with sufficient precision to yield valuable information about student learning and program quality.

Other jurisdictions have faced similar implementation challenges as Ontario when attempting to measure learning outcomes and have developed strategies to address them (OECD, 2013). The revamped Collegiate Learning Assessment Plus (CLA+), used by hundreds of institutions in the US to measure their impact on student skill development, generates more precise estimates of student outcomes than their previous version of the tool.

Another HEQCO research project currently underway offers a promising model for continued experimentation along this line, with a focus on higher-order cognitive skills. In 2012, HEQCO launched a request for proposals for institutions to develop and test learning outcomes measurement tools; six institutions were selected (Durham College, George Brown College, Humber College, University of Guelph, Queen's University, University of Toronto) and have since published summaries of initial progress:

- The University of Guelph piloted an online assessment tool for learning outcomes in their Bachelor of Arts and Science, and Engineering programs in 2012-2013 and are currently in the process of using the knowledge gained in this pilot project to articulate all the learning outcomes assessed in a full program of studies (B.Eng), across all seven majors, from year 1 to year 4 (HEQCO, n.d.).

- George Brown has developed a common assessment tool for communication and critical thinking, which can be adapted for use in any course, and is currently working on teaching and learning strategies which can be adapted to build critical thinking and communications skills into curricula, using the assessment tool. (HEQCO, n.d.a)

- Queen's University is developing and/or testing a range of assessment tools and working to incorporate learning outcomes assessment into curricula in the faculties of arts and science and engineering and applied science (HEQCO, n.d.b).

One promising anecdotal finding from the initial summaries on the consortium is that faculty have been enthusiastic and that interest in the project has grown since its inception (HEQCO, n.d.; HEQCO, n.d.a.). The bottom-up, institutionally driven character of the HEQCO consortium makes it the most promising path towards making progress on measuring the learning outcomes of Ontario postsecondary education.

Information for students

As in other jurisdictions, there is a concern in Ontario about students' transitions to the labour market. Ontario graduates report having difficulty finding reliable career advice (Sandell, 2011), and they are taking longer to find stable employment. While there is considerable data in Ontario on postsecondary education, publicly released data is fragmented and not easily comparable. This makes it difficult for students to assess the costs and benefits of pursuing different career paths. Research suggests that students do make use of the limited information they have through their field of study choices (Usher, 2014).

Students require information to hone their postsecondary experiences with their future careers in mind. At the most basic level, jurisdictions are offering prospective students user-friendly dashboards of labour market outcomes, graduate satisfaction and other data allowing comparison between programs, to help them make better decisions about what and where to study.

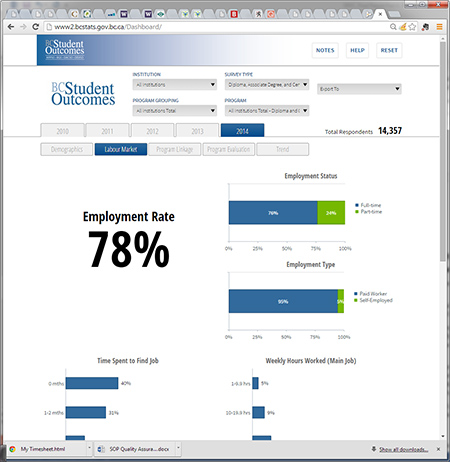

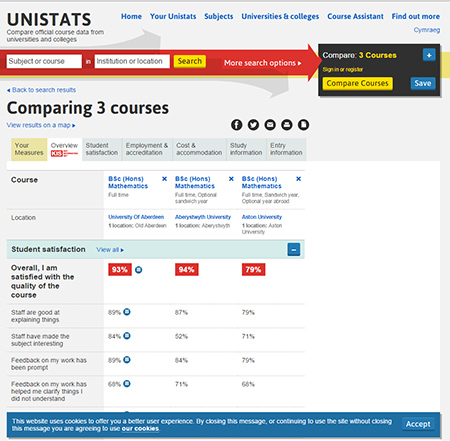

In two jurisdictions (British Columbia and England) we found comprehensive graduate outcome information in a user-friendly online dashboard. British Columbia's Student Outcomes Executive Dashboard allows prospective students to access graduate outcome data at individual program level, including employment rates, average salaries, satisfaction, and relatedness of work to their field of study. England's Unistats allows prospective students to compare programs from multiple institutions on a range of variables including average salaries, employment rates, program fees, and satisfaction.

Examples of dashboards from SRDC's scan of other jurisdictions

British Columbia's new Student Outcomes dashboard:

- Presents annual graduate survey data for all publicly funded postsecondary programs in an intuitive, user-friendly way.

- Includes tabs for: Demographics, Labour Market, Program Linkage (employment relatedness), Program Evaluation (program satisfaction), and Trends in outcomes.

Figure 68: Snapshot of British Columbia's Student Outcomes dashboard

The United Kingdom's UNISTATS comparative dashboard:

- Unistats allows prospective students to compare programs from multiple institutions on a range of variables including average salaries, employment rates, program fees, and satisfaction.

- Prospective students can customize their search criteria to compare programs only on the things that matter to them.

Figure 69: Snapshot of the United Kingdom's UNISTATS prospective student information tool

1 In 1998, the European Commission and Cedefop set up the European forum on transparency of vocational qualifications to bring together social partners with representatives of national training authorities around the issue of transparency. The work of the forum resulted in the development of two documents (The European CV and the Certificate Supplement) and a network of National Reference Points for Vocational Qualifications. The Europass includes three other documents, developed at European level in the late 1990s: the Diploma Supplement, the Language Supplement, and Europass Mobility.